Christ is risen!

As promised, by God’s grace, I’d like to begin a series of posts regarding what are now known to the Copts as “inaudible prayers”. The concept of secret or inaudible prayer has been treated rather extensively in the Eastern Orthodox tradition as well as the Western tradition, but has yet to be discussed to the same degree (to my knowledge) in the Coptic Rite. I hope these few posts ignite a desire within our community for our liturgical worship and ensure a deeper reading and theological understanding of our dwelling with God in the Church.

Thus far, I’ve divided the series into 5 posts which titled:

On Mystical or Secret Prayer(s) in the Coptic Rite

1. Liturgical Theology 101: Basic Liturgical Principles and Development of Secret Prayer

2. Prayers of the “Offertory”

3. Prayers of the Liturgy of the Word 1: The Incense, Epistles, and Acts

4. Prayers of the Liturgy of the Word 2: The Gospel and the Ministry

5. Prayers of the Anaphora

Disclaimer: Each and every one of these posts can be expanded into full academic papers and discourses. These posts are not necessarily meant to go into every minute detail, but are intended to provide general knowledge and insight into the 1) basic structure of Coptic Liturgy, 2) older and more authentic praxis, 3) current liturgical state and the possible theological/practical issues therein.

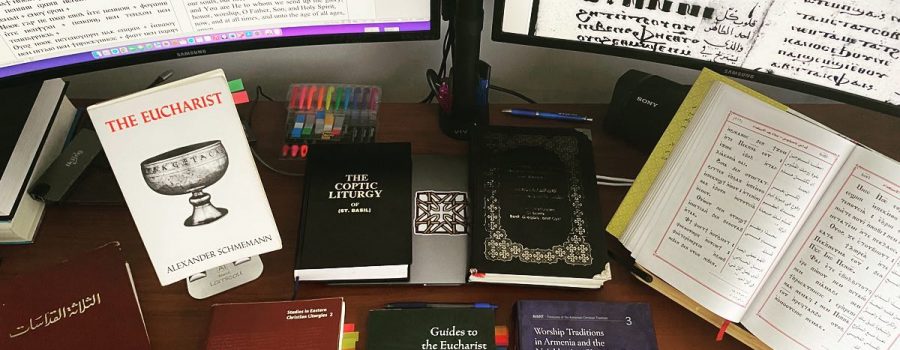

I’ll do my best to provide my resources as the posts go on; a few that will be referenced or at least extrapolated from:

A. Guides to the Eucharist in Medieval Egypt by Ramez [Fr. Arsenius] Mikhail — a translation of three principle Arabic commentaries on Coptic Liturgy:

• Misbah al-Zulmah…, Abu al-Barakat ibn Kabar

• Al-Jawharah al-Nafisah…, Yuhanna ibn Sabba’

• Al-Tartib al-Taqsi, Pope Gabriel V

B. Two of the oldest extant Bohairic Coptic Euchologia (both being 13th century documents)

• Bodl.Hunt.360

• Vat.Copto.17

C. A number of other liturgical resources:

• Introduction to Liturgical Theology, Fr. Alexander Schmemann

• The Eucharist, Fr. Alexander Schmemann

• Beyond East and West: Problems in Liturgical Understanding, Fr. Robert Taft

• Historical Evolution of the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom (Several Parts in Series), Fr. Robert Taft

• Eucharist – Theology and Spirituality of the Eucharistic Prayer, Louis Bouyer

For some basic reading on the matter (general info, but written from an Eastern liturgical perspective):

1. https://www.orthodoxwitness.org/the-practice-of-reading…/

2. https://churchmotherofgod.org/…/2266-reasons-for-secret…

Now, let’s begin!

Liturgical Theology 101: Basic Liturgical Principles and Development of Secret Prayer

If we as [Orthodox] Christians believe that we are the Body of Christ then, by default, our gathering in and of itself is “sacramental”; in order for us to become this one Body of Christ our coming together must be one that sanctifies us and changes us and manifests us as the Church, the holy nation of God. Thus, it is the assembly, the act of gathering itself, that realizes, or for ease of understanding, enacts the Church, the living witness to the passion and resurrection of the LORD, the bride waiting for his return. Hence, we pray multiple times, “Remember, O LORD, our assembles—bless them!” Following this train of thought, if our assembly is of such magnitude and significance, then what we do when we gather, must also reflect the same concept and reflect the same level, if not a higher level, of import. As is exhibited in the Gospel of Luke, Chapter 24, the disciples on the road to Emmaus met with Christ; he exegetes the Scriptures to them, explaining how Moses and all the prophets spoke concerning Him, and then ONLY in the breaking of the bread do they know that He is LORD. Thus, it is within the liturgy itself that we encounter our God, and through the Eucharistic prayers he actually abides within us and we in Him. Therefore, the very mind and method exhibited in the liturgical life of the Church interprets the Word of God and makes Him known in the world.

As a general rule, “lex orandi lex est credendi” which translates to “the rule of prayer is the rule of faith”— a principle followed by the early Church that has been heavily “reintroduced” or reiterated by Fr. Schmemann.

I’d like to unpack this for us Copts in layman’s terms: “What we pray is what we believe”; this means that what we do (the prayers and readings we recite, the actions and movements that we make, the basic structure that we follow, the hymns that we chant, the very nature of our worship) is what we believe (who we understand God to be, what we and the entirety of the world are with respect to Him, how we ought read His Word, and the method by which we live); again, God reveals Himself in the liturgy of the Church. If you want to know who God is, how He loves us and we ought to love and worship him, then you must come to understand that He has made it so that all this is known through the Church, through liturgy. Liturgy is THE act of the Church, not an act amidst a bunch of other social services.

Moving forward, the next important concept is this: There is nothing prayed by the Church that isn’t intended for the whole Church. That which the priest prays is on behalf of all, and is to be participated in by all—not necessarily by utterance, but in the lifting of the heart and mind towards God. There are no actions or words or hymns or readings that are designated only for the elect few or to be performed privately, because the entirety of the prayer is the work of the entirety of the Church; the term ⲗⲉⲓⲧⲟⲩⲣⲅⲓⲁ itself means “work of the people” or rather the “corporate action”. I hope you can see where I’m going with this ![]() So, as an example, what we now call “vespers praises” which is most likely attended by maybe 2 or 3 chanters at most who go early and sing a few hymns before the priest enters the church and unveils the altar is actually not a thing; all of those praises were originally part of Vespers itself (something which will be written about extensively in the coming Coptic English Psalmody) —meaning that the totality of the Church (the priest, the deacon, and the laity) are to be present, praying together, chanting together, listening together, being present in mind, body and spirit. The same applies to the matins doxology ⲡⲓⲟⲩⲱⲓⲛⲓ and the psalms of the hours, and responses of the deacon. All of these prayers are for the whole Church, and are to be internalized by the whole Church.

So, as an example, what we now call “vespers praises” which is most likely attended by maybe 2 or 3 chanters at most who go early and sing a few hymns before the priest enters the church and unveils the altar is actually not a thing; all of those praises were originally part of Vespers itself (something which will be written about extensively in the coming Coptic English Psalmody) —meaning that the totality of the Church (the priest, the deacon, and the laity) are to be present, praying together, chanting together, listening together, being present in mind, body and spirit. The same applies to the matins doxology ⲡⲓⲟⲩⲱⲓⲛⲓ and the psalms of the hours, and responses of the deacon. All of these prayers are for the whole Church, and are to be internalized by the whole Church.

These basic theological concepts are embedded in Scripture and early Church thought (many quotes from Church Fathers and ancient Christian texts in the links above)—I’ll just paste a few here:

• St Paul presupposes that the prayers were offered aloud so that a response “Amen” may also be offered (1 Cor 14:16–17)

• St Justin Martyr says that the celebrant, “sends up praise and glory to the Father of the universe through the name of the Son and of the Holy Spirit and offers thanksgiving at some length that we have been deemed worthy to receive these things from him. When he has finished the prayers and the thanksgivings, the whole congregation present assents, saying, ‘Amen.’ ‘Amen’ in the Hebrew language meaning, ‘So be it.’” You can see here that the celebrant is doing the work as is given to him by the people, and what he does, he does on behalf of all, as they all respond in turn.

• St John Chrysostom continues the same notion of the Eucharistic prayers being audible, “In the most awful mysteries themselves, the priest prays for the people and the people also pray for the priest; for the words, ‘with thy spirit,’ are nothing else than this. The offering of thanksgiving again is common: for neither does he give thanks alone, but also all the people.” (Sermon 18 on Second Corinthians)

• Emperor Justinian (March 26, 565 AD)

We command that all bishops and presbyters pronounce the prayers of the Divine Anaphora and Holy Baptism not secretly, but with a voice that can be heard well by the faithful people, so that the minds of the listeners would be moved towards greater compunction and thanksgiving to God. It is fitting that prayers to our Lord Jesus Christ our God, with the Father and the Holy Spirit, in all occasions and at other services be pronounced loudly [meta fōnēs]. Those refusing to do so will give their answer before God’s throne and if we should find out, we will not leave them without punishment. (137th Novella)

We have fallen so far from this understanding in our current practice, that our people typically enter the Church, and having no idea what is actually happening (since almost half of the liturgy is performed silently by the priest, especially in the Liturgy of the Word) they resort to personal prayer, individualistic requests of all kinds, as opposed to understanding that their presence itself is part of the mystery of God’s presence with his people. We often see the priest praying one thing, while the people have their ⲁϫⲡⲓⲁ open reading other things, or now, as a result of unawareness of what the priest is doing, we’ve begun to incorporate prayers from elsewhere (whether it be from other jurisdictions or from the ⲁϫⲡⲓⲁ itself or even otherwise) into our eucharistic prayers AS IF THE LITURGY THAT WE HAVE IS INCOMPLETE OR LACKING (I have no words for this other than the Arabic, “ya lahwy” or on a particularly rough day, “ya kharaby” lol). All of this has occurred because such a large portion of our liturgy has become silent (though we’re always singing, while the priest is actually praying other things) and as a result, we’ve lost the underlying understanding of what we’re praying for. As some might say, it’s these inaudible prayers that are the most theological rich and beautifully heartfelt.

By now, you must be asking, so how in the world did this shift in understanding occur and how did this amount of prayers become silent or secret, in the Coptic Rite?

I’d like to venture a few possible thoughts (the order in which I’ve placed them is not linear, but more or less that of complexity):

1) Attendance – For certain prayers, like those of the preparation of the altar, attendance might be a factor. In many parishes, this occurs so early within the service that there are very few congregants present. It is likely that the priest may not pray them aloud, and just read them to himself, while a deacon (or a minor order) handles other tasks.

2) Time – Almost every Copt has heard the statement, “mafeesh waqt” مفيش وقت when it comes to almost anything liturgical. Throughout the centuries, our church has suffered much persecution, times of prayers were limited, churches were closed, and yet even amidst all of that we somehow managed to maintain (only by God’s grace really) whatever is left of our tradition. But, apparently, now, in 2022, there’s no time; when we live in the diaspora, where our freedom is celebrated and our tradition is respected by peoples from the corners of the earth, now we have no time to sing, no time to pray, no time to even read the words in our books. In some cases, we find that the priests begin praying their next section silently to themselves while the deacon and the people respond, so that by the time the laity have said, “LORD, have mercy!” the priest is already finished with the next petition…Though this excuse of time constraint definitely has an impact on some of the secret prayer that occurs in liturgy, it doesn’t explain how this large number of prayers has become silent…for this reason, we also have to take other factors into account.

3) Language – Oftentimes, you may find that our euchologia tell us that the priest prays one thing while the deacon or reader interprets the Coptic reading. In other words, when Coptic was the only language used to chant the readings of the Epistles etc. the prayers that followed were said on their own. However, when the readings were then interpreted (or in today’s terms, translated) into Arabic, the priest continued his prayers but recited them silently as to allow the reading to be heard and not disrupt the time or the order.

4) “to its end” – Many liturgical prayers end with similar or familiar conclusions. In these cases, we see that Coptic manuscripts typically do not rewrite these conclusions, but abbreviate them with things like: ⲛⲉⲙ ⲡⲥⲱϫⲡ “and the rest”, or ϣⲁ ⲡⲉⲥϫⲱⲕ “to its completion”, or ϣⲁ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ (abbreviated sometimes as ϣ︦ⲃ︦ⲗ︦) “to the end”. In our current books, you may find these things italicized indicating that they aren’t said aloud, although that was never indicated in our manuscripts. It was just that they did not rewrite the same thing multiple times. Now that we have apps, a lot of these prayers are minimized and can actually be turned off so as to not be displayed at all—completely detrimental to the liturgical experience as one is not even exposed to the prayers which are prayed on their behalf.

5) Replacement with Hymns – In both the Eastern tradition and the Coptic Rite, hymns have developed that have overtaken the prayers of the priest. Within our tradition, Hymns of Incense such as ⲛⲑⲟ ⲡⲉ ϯϣⲟⲩⲣⲏ ⳾ ϣⲁⲣⲉ ⲫϯ ⳾ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲉⲧⲁϥⲉⲛϥ and the very recent and disorienting ⲭⲉⲣⲉ ⲛⲉ ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ have covered up the beautiful and unbelievably rich and important prayers of incense, some of which are prayers of confession offered on behalf of the people (as there was a time in our history when confessions took place as the priest passed through the congregation with the censer). I believe to some extent this also has to do with time constraint, but each of these prayers alone does not take more than a minute or so to recite aloud, so even if this occurred in the past due to time constraint, we really do not have an excuse now…

6) Popular Piety and/or Clericalism – it is historical fact, that especially during the Middle Ages, the Church as a whole underwent significant struggles with regards to clericalism. This caused a division between the clergy of the church and the laity, especially within the liturgical work. Many prayers were reserved only for the clergy, conducted behind the curtain, and in many traditions to this day, we find that communion is reserved for the priests and the congregation practices abstinence even from the holy mysteries (a topic which has also been extensively debated in the Eastern tradition and thankfully has been done away with to a great degree). Popular piety also has a major effect on our liturgical worship; such things like the “no greeting rule” during Holy Week—which somehow extends a day every year—began solely as a liturgical function of not greeting in the kiss of peace, to not greeting during the offering of incense, and then turned into do not even look at the person next to you. These practices arise from cultural expressions or understandings of certain concepts and impact our tradition over time. We may hear a lot of “unworthiness” or “who am I?” explanations as to why we don’t hear certain prayers aloud, or why certain practices have come about, and in most scenarios, these answers do not suffice a logical and consistent interpretation.

7) Disciplina arcana – that the mysteries of the faith should not be revealed to those who are not initiated into the Church. In the early Church, catechumens were asked to leave prior to the prayers of the Anaphora itself, to prevent the mysteries of the church from being revealed to those who had not yet been received into the Church through baptism. Because the catechumenate fell away for the most part (at least in its early form), a mimicry came about in the form of a separation between those of “higher understanding/status” (clergy) and those of the ordinary members (laity) such that prayers regarding the mysteries were shielded from them. Ties back into clericalism, but finds its roots in an older understanding within the church.

![]() Influence of other Oriental or Eastern Churches – it is highly likely that our tradition has been influenced by that of other jurisdictions in this regard given the number of groups and individuals from other churches that took refuge in Egypt, as well as the exchange of prayers between the Churches that continued/continues to occur to this day.

Influence of other Oriental or Eastern Churches – it is highly likely that our tradition has been influenced by that of other jurisdictions in this regard given the number of groups and individuals from other churches that took refuge in Egypt, as well as the exchange of prayers between the Churches that continued/continues to occur to this day.

9) Liturgical rubrics – Perhaps the most interesting and compounded aspect of this secret prayer (to me) is the use of the word ⲙⲩⲥⲧⲓⲕⲱⲥ. ⲙⲩⲥⲧⲓⲕⲱⲥ, coming from the word ⲙⲩⲥⲧⲏⲣⲓⲟⲛ, literally means “mystically” or “relating to the mysteries”, and also “private” or “secret”. When the word is translated to Arabic, it is frequently written as سراٌ which may have caused some more convolution for us, since the Arabic term (as far as I understand it) has more to do with secrecy and being “to ones self” than it does to do with mystery. The lack of instruction and continuity of font and text in the earliest manuscripts of the Coptic Euchologion support the idea that none of these prayers were recited inaudibly at all; in fact, as is seen in Fr. Arsenius’, “Guides to the Eucharist in Medieval Egypt” the majority of the prayers that are now secret, were described as being recited aloud, and responded to by both the deacon and the people as a whole. Interestingly, the only prayer mentioned to be “ سراٌ” in Ibn Sabaa’ or in Bodl.Hunt.360 (in Basils’ Liturgy) is that of the epiclesis in which we invoke the descent of the Holy Spirit upon us and upon the fits, and it is only written in the Arabic rubric, the Coptic only including: ⲟ ⲓⲉⲣⲉⲩⲥ ⲉⲡⲓⲕⲗⲏⲥⲓⲥ. As the understanding of the word itself took on many different forms, it is possible that prayers that had to do directly with the mysteries became completely secret as opposed to pertaining to the mysteries.

Of note, in the last century, we have audio recordings of many priests and bishops still reciting these prayers aloud! In fact, the euchologia of the church to this day place the deacon responses in between some of the prayers that are said inaudibly. How would the deacon respond if he hasn’t heard the priest?——I will attempt to go through this meticulously in later posts. Listen to the Late Bishop Lukas (at minute 6 and on, and again at 1:14:27 you can hear HG still reading the prayers aloud but the chanters are screaming over him) who prayed the currently inaudible prayers aloud IN COPTIC NONETHELESS—what a boss!?: https://app.box.com/s/jj6rqk9vqpblugsarlkbmw7xxm2k1my2

Of course, there may be other factors other than what I’ve summarized here. Moreover, different factors may have effected change for different prayers; it’s not a one size fits all type of development. Throughout the rest of this series, I will do my best to go through each of the prayers in more detail and of course their spiritual significance, but in order for any of that to make sense, I had to give this introduction. If you read through the links I included above you can also see the interpretations of other writers and scholars, including quotes from some of the Fathers and Councils of the Church and their varying opinions on the matter. Regardless of whether these prayers continue to be prayed secretly or if they return to their proper public status, it is excruciatingly important for all of us to take up that which is ours and to know what is prayed by the Church, for the Church, and for the sake of the whole world.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.