After a lengthy hiatus, and more or less pending another more permanent one, I write today another post about one of our most well-known and dear chants: ⲙⲁⲣⲉⲛⲟⲩⲱⲛϩ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⳾

ⲙⲁⲣⲉⲛⲟⲩⲱⲛϩ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ is comprised of 8 primary stanzas and, in its earliest forms, 1 intercessory stanza for David the Psalmist (ONLY). The text is labeled as ⲯⲁⲗⲓ ⲛ̀ⲇⲁⲩⲓⲇ “Psali of David” in most psalmody manuscripts, though most common books now mistakenly use the term ⲗⲱⲃϣ. Within the Bohairic Psalmody, this hymn is chanted after the Second Canticle (Psalm 135); in other rites, however, it is used as a processional hymn (funerals, weddings, etc.), and on Holy Saturday as a conclusion to the entire book of the Psalter (Psalms of David). Interestingly, there are 3 or 4 different melodies that can be chanted on this text, but I won’t get into that too much today. It is of the UTMOST IMPORTANCE for us to analyze and understand the text itself, its structure, and how it is employed and purposed within the Rite as a whole. Let’s take a look at the text (translation is my own as part of the Coptic-English Psalmody Project).

Let us give thanks • unto Christ, our God, • with the melodist, • David the Prophet, •

for He made the heavens • along with their hosts, • and founded the earth • upon the waters.•

These great stars/lights, • the sun and the moon, • He set them to illumine • in the firmament. •

He brought forth winds • out of His treasures; • they blew into the trees • until they blossomed. •

He poured rainfall • on the face of the earth, • until it sprouted • and gave its fruit. •

He drew water • out of a rock • and nourished His people • in the wilderness. •

He created man • after His likeness • and His image • that he may bless Him. •

Let us praise Him, • and exalt His name, • and give thanks to Him, • for His mercy is forever. •

Through the prayers • of David the Psalmist, • O LORD, grant us • the forgiveness of our sins. •

Let’s go through some notes on the text:

1) The use of the Coptic ⲟⲩⲱⲛϩ implies (among other things) both giving thanks, and confessing, in the same way the Greek word εξομολογεισθε carries both connotations. These definitions stem from the connection between acknowledging/admitting something. In Robert Alter’s translation of Psalm 135, he notes that the text acclaims, that is to praise enthusiastically and publicly, God as creator of heaven and earth and then moves rapidly through God’s intervention in history in the Exodus and the conquest of Canaan. Following this line of thought, confessing and acknowledging our God wholeheartedly is offering Him thanksgiving and praise.

2) Notice the subject of our thanks—Christ our God. The juxtaposition of this hymn with Psalm 135 is not haphazard. The psalm itself is clearly about the God of Israel, the Creator, and all the mighty deeds that He wrought in His creation. The placement of ⲙⲁⲣⲉⲛⲟⲩⲱⲛϩ after this psalm is a clear confession that Christ our God is the subject, the Creator, in Psalm 135. In this way, we see how the Psalmody and its contents are meant to exegete/interpret the Scriptures. David the Prophet is also mentioned because the Church attributes the Psalms to David, and there is a functionality between the book of David, and David himself, in the same way that the gospels are understood to be Christ himself speaking, and the same applies to the epistles of Paul and the rest of the OT.

3) There is a sort of movement within the text between God’s actions towards His creation and their response. It is not an exactitude, but present nonetheless. He sets the sun and the moon and they shine, he brings forth the winds and they blow into the trees (Notice that the current translations have “He breathed unto the trees”. This is simply untrue as God only breathed into man. In addition, the more prevalent Coptic text is ⲁⲩⲛⲓϥⲓ which is plural third person, not ⲁϥⲛⲓϥⲓ—though both are attested to in some cases, yet the Arabic translations at the time of transcription of the texts speak of the winds themselves blowing into the trees. He pours rainfall, and the earth sprouts forth. He draws water, and it nourishes his people (an argument can be made here as to whether the ⲁϥ in ⲁϥⲧⲥⲓⲟ is referring to Christ or to the water, but that’s another topic).

4) The Coptic use of ϣⲁⲛⲧⲉϥ or ϣⲁⲛⲧⲟⲩ translates literally as “until…”. Though it may sound unfamiliar the modern ear, this phrase is used quite commonly in scripture and does not necessarily evoke a temporality, or an ending (but this note is just for completeness’ sake)

5) You may notice ⲁϥⲧⲥⲓⲟ ⲙ̀ⲡⲉϥⲗⲁⲟⲥ as opposed to ⲁϥⲧⲥⲟ ⲙ̀ⲡⲉϥⲗⲁⲟⲥ; not surprising that one iota dropped out of the text over the years, but, important to note that the word ⲥⲓⲟ is not just to give drink but to satisfy or nourish.

Now we turn to the meat of this post—Stanza 7: “He made man…”

The reason this post has come up is because I’m quite honestly very frustrated—frustrated with the way we as a community and as an institution handle our liturgical and theological texts with all carelessness, sloppiness, and in unnecessary hastiness. And I am quite sorry to have to be so frank with my words, but I am clearly not one to be ambiguous or to hide the truth.

Most translations in our English books included a rough translation, “He made man, in His image, and His likeness, that he may praise Him.” While you may notice slight differences in the translation that I have above, the movement of the text is the same: God creates man with the purpose/ability/function of praising Him. There is much to say on the theology embedded in this simple statement, but I will get to that in a few moments. In a recent update, Coptic Reader, (at the behest of a member of the hierarchy who is not from the US and is not a native English speaker) “decided” to change the English translation of stanza 7, AT FIRST to, “He made man, in His image, and His likeness, that He may bless Him.” — HUH? God made man to bless Himself? (Let’s say that was a typo, this still raises a number of issues) — and then to “He made man, in His image, and His likeness, that He may bless him.” Because of this unnecessary and understudied alteration to the text, the focus has shifted from man’s action, his vocation as a creation of God, to God simply bestowing on Him a blessing—that being made in His image is merely a gift with no action on man’s part in response. So what is the basis then for this change?

If my information is correct, the argument to change this translation is based on the use of the Coptic word ⲥⲙⲟⲩ. There are a plethora of forms of the word ⲥⲙⲟⲩ as you will see in the images from Crum’s dictionary that I’ve attached here, including, ⲥⲙⲟⲩ ⳾ ⲥⲙⲁⲙⲁⲁⲧ ⳾ ⲥⲙⲁⲣⲱⲟⲩⲧ (which are the more commonly seen ones) and ⲥⲙⲁⲙⲉ ⳾ ⲥⲙⲁⲩⲁⲧ ⳾ ⲥⲙⲁⲙⲉⲧ which are rarely seen now in our liturgical corpus. Ⲥⲙⲟⲩ also has a number of definitions: (v) to bless or to praise, ( n ) a blessing or praise, gift, benevolence, abundance, treasure, even salute. The word is interchangeable in some cases with another Coptic word that you are familiar with—ϩⲱⲥ for praise, song etc.. In translations of the Scriptures the word ⲥⲙⲟⲩ is used to translate the Greek ευλογεω or αινεω and even the aforementioned εξομολογεω. In a similar vein, the Hebrew word for bless לברך berákh (similar to the Arabic بارك barik) also has something to the force of “praise” though it also retains connection to kneeling, and/or showing respect. Now, these words are used all throughout the Scriptures, especially in the Torah and the Psalms; You may encounter formulas like “Blessed be/is God” or “we have blessed you” or “blessed is the fruit of your womb” or “Bless God” and the one that we Copts know very well from our 3rd Canticle “Bless the LORD” from Daniel 3. Returning now to the argument for changing the translation, it was suggested (without any substantive work/reasoning) that when the word bless is used from man to God it automatically means praise and thus, based on the modern translation of the Arabic, the entire stanza must be speaking of God blessing man, since man shouldn’t be blessing God, but rather that God creating man was a blessing for man, that He created us because He loved us (which is true, but completely ignores the use and purpose of the “in His image and likeness” clause here. Of course this line of thought is non-biblical, as well as unsupported in Patristic writings, that man does not “bless God”.

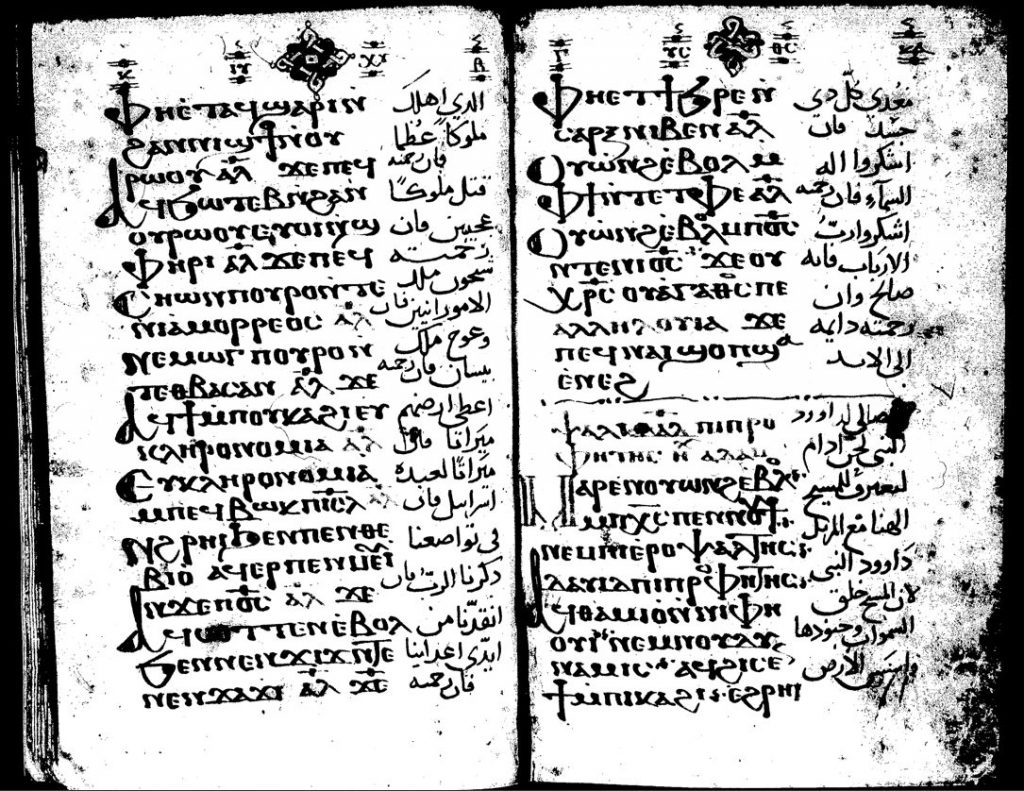

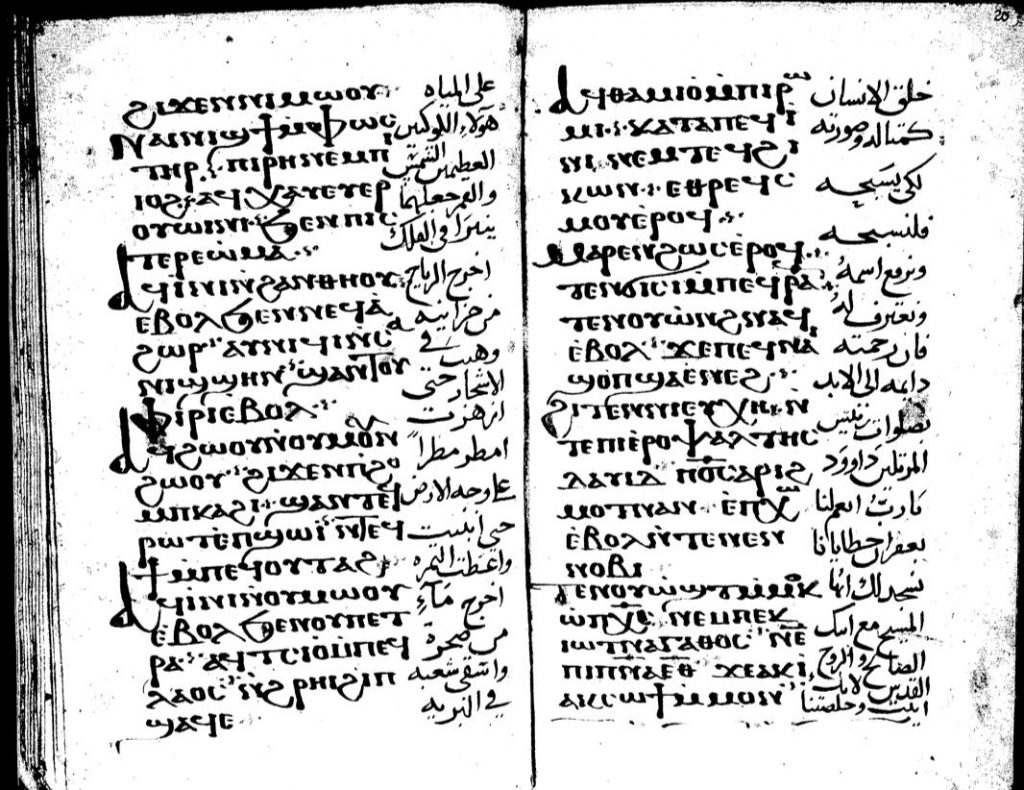

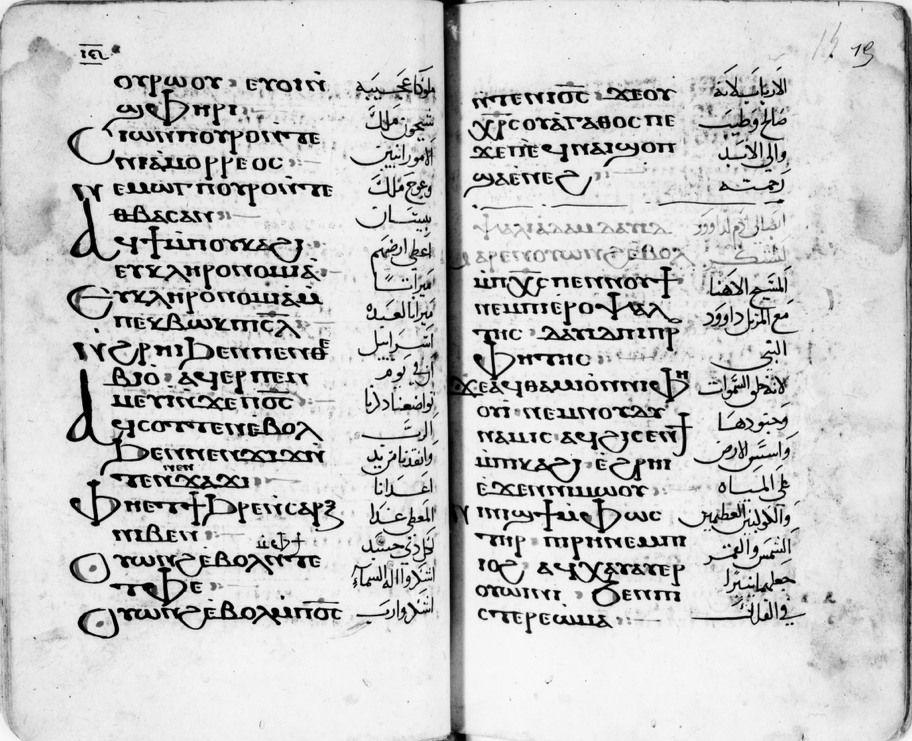

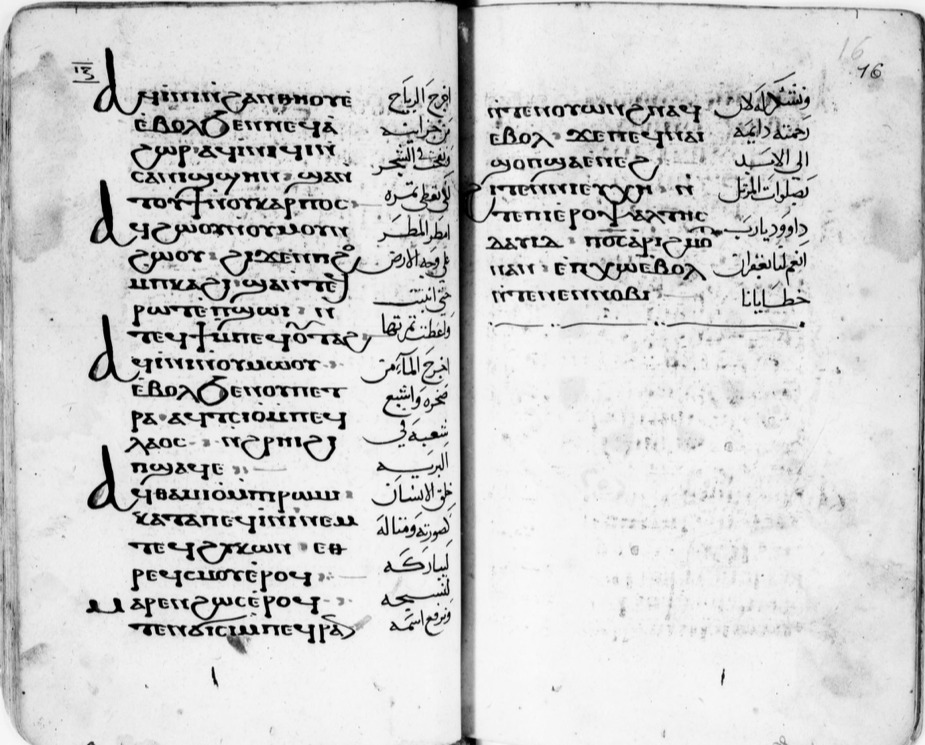

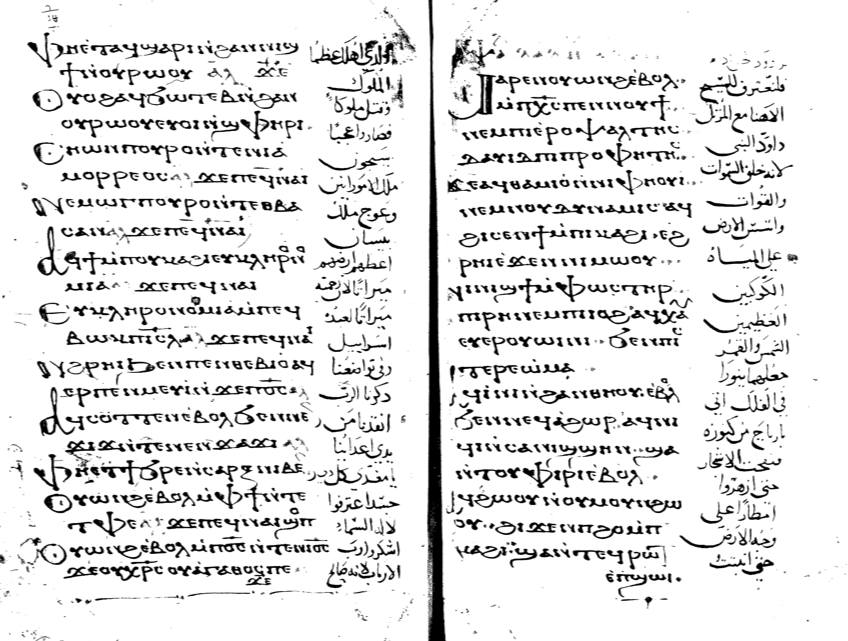

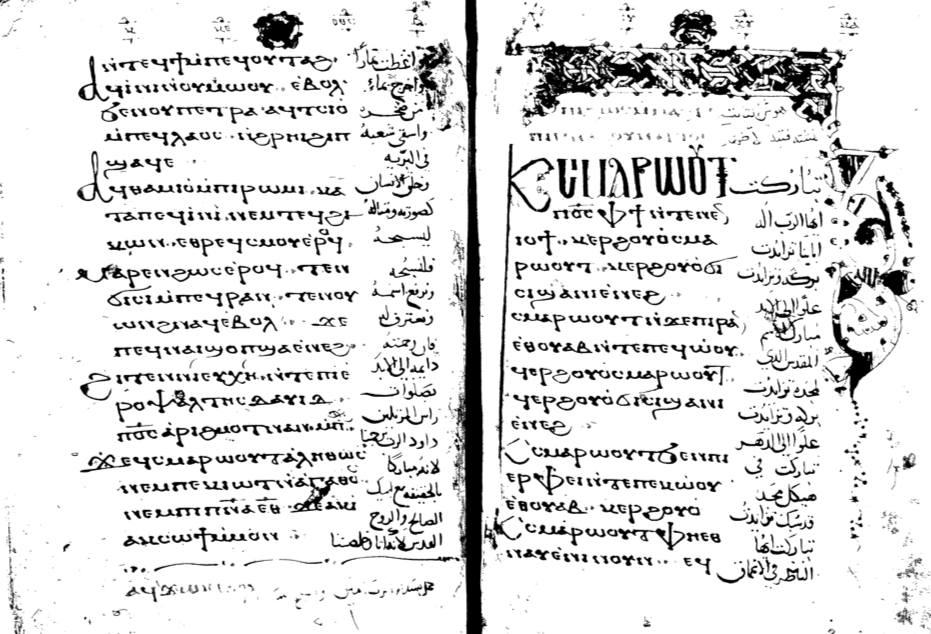

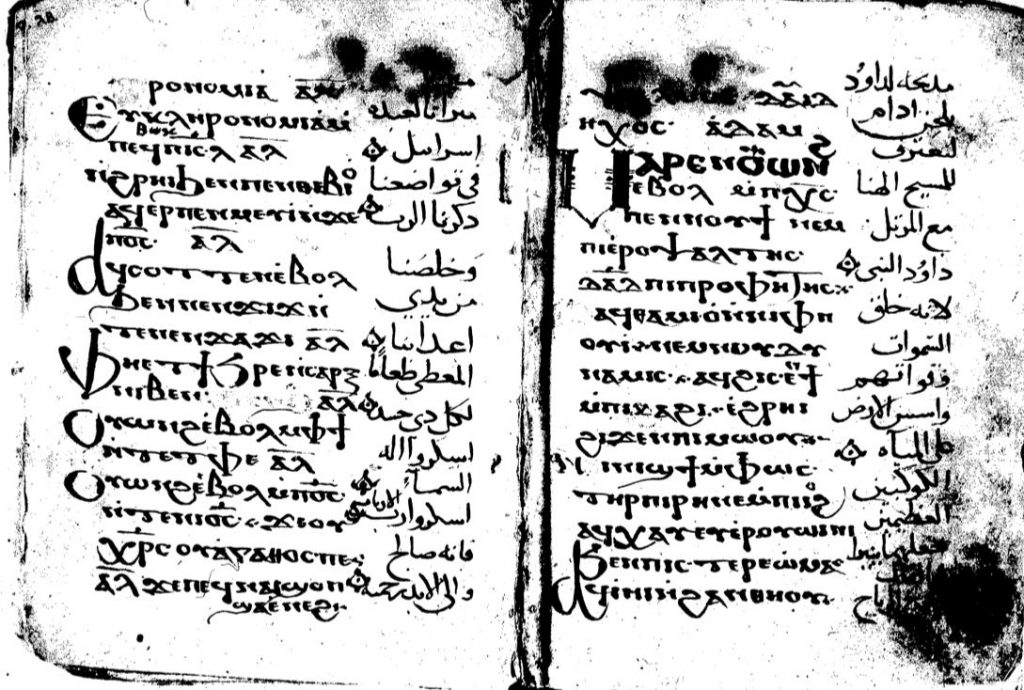

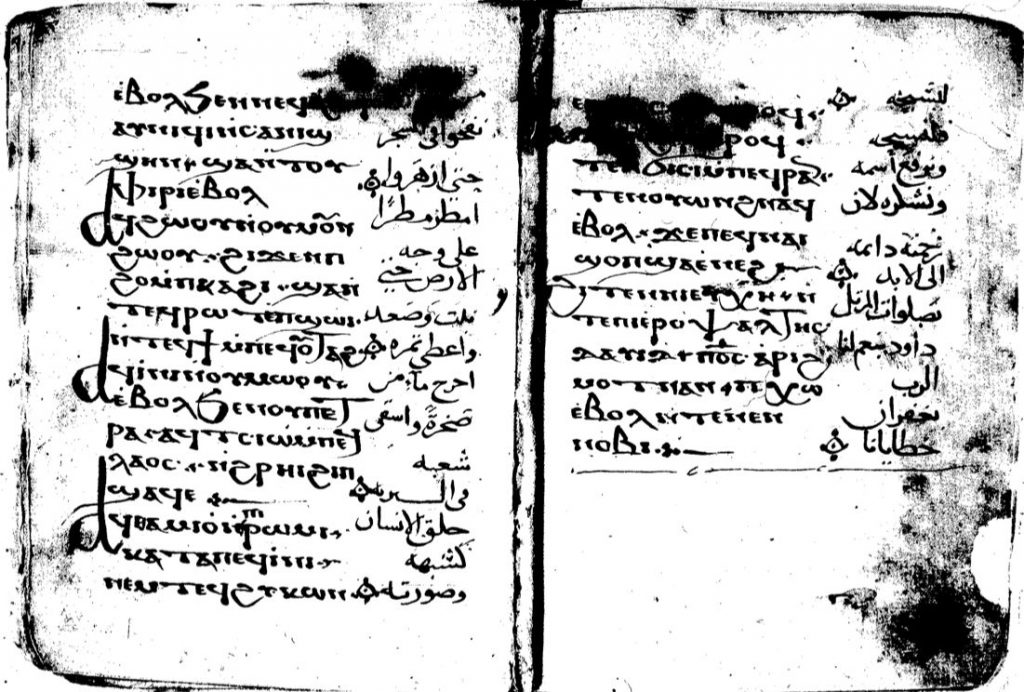

Of the five earliest extant manuscripts of the Bohairic Psalmody, 3 of them translate the last stichos of the stanza as ليسبحه “that he may/to praise Him”, whereas one includes no Arabic translation, and the other writes ليباركه “that he may bless Him”. If the Him/him issue is unclear because of the modern Arabic translation, then the older Arabic is much more clear. To my knowledge, the verb سبح is never used as God praising man. It is always used as سبحوا الرب etc. As such, the understanding of the transcribers at the time suggests that the stanza speaks of God creating man in His image so that man might bless/praise God, NOT the other way around. Furthermore, the following stanza makes it abundantly clear as it then calls us to praise God, exalt His name, and give thanks/confess/acclaim Him for His mercy is forever! Thus, the entirety of the hymn culminates in us fulfilling our purpose as God’s creation by praising Him; it is as though the text walks us through creation as a whole and dictates to us our place in it.

Do we have Patristic support for this claim? Certainly!

If we look at the writing of our holy father, Abba Athanasius the Apostolic, in his “On the Incarnation” we read,

“For God is good, or rather the source of all goodness, and one who is good grudges nothing, so that grudging nothing its existence, he made all things through his own Word, our Lord Jesus Christ. Among these things, of all things upon earth he had mercy upon the human race, and seeing that by the principle of its own coming into being it would not be able to endure eternally, he granted them a further gift, creating human beings not simply like all the irrational animals upon the earth but making them according to his own image (cf. Gen 1.27), giving them a share of the power of his own Word, so that having as it were shadows of the Word and being made rational, they might be able to abide in blessedness, living the true life which is really that of the holy ones in paradise.”

Here, God creates man in His own image as a gift, yes, of being rational beings, being λογικοι, that is, to be patterned or ordered upon the Logos, the Word, Christ Himself. By being made rational, we are able to abide in blessedness, living the life of the holy ones. What is this life of the holy ones, other than the fulfillment of their vocation as creation, blessing God. And again, Athanasius says,

“Since, then, human beings had become so irrational and demonic deceit was thus overshadowing every place and hiding the knowledge of the true God, what was God to do? Be silent before such things and let human beings be deceived by the demons and be ignorant of God? But then what need was there in the beginning for human beings to come into being in the image of God? He should have come into being simply irrational, or having been rational not live the life of the irrational creatures. What need at all was there for him to receive a notion about God from the beginning? For if he is not now worthy to receive it, neither should it have been given him from the beginning. Or what profit would there be to the maker God, or what glory for him, if human beings, brought into being by him, did not revere him but reckoned others to be their makers? For God would be found creating them for others and not for himself.

Moreover, a king, being human, does not permit the lands established under him to pass to and serve others, nor does he abandon them to others, but he reminds them with letters, and often enjoins them by friends, and, if need be, comes himself, shaming them by his own presence, only so that they not serve others and his work be in vain. How much more will God allow his own creatures to not be led astray from him and serve things that do not exist? In particular, since such error is the cause of their destruction and disappearance, it was not right that those who had once partaken of the image of God should be destroyed. What then was God to do? Or what should be done, except to renew again the “in the image,” so that through it human beings would be able once again to know him? But how could this have occurred except by the coming of the very image of God, our Savior Jesus Christ? For neither by human beings was it possible, since they were created “in the image”; but neither by angels, for they were not even images. So the Word of God came himself, in order that he being the image of the Father (cf. Col 1.15), the human being “in the image” might be recreated. It could not, again, have been done in any other way, without death and corruption being utterly destroyed. So he rightly took a mortal body, that in it death might henceforth be destroyed utterly and human beings be renewed again according to the image. For this purpose, then, there was need of none other than the Image of the Father.”

The underlying motif here in Athanasius’ writing is the idea of man’s restoration—that the human being was recreated through the Word of God in whose image he was made, and that being renewed through the Image of the Father, man may return to his initial state. Some might ask me what is the difference? I will attempt to elaborate further. Though man being created in God’s image was a blessing to man, it is not this giving of the gift that Athanasius focuses on but rather how this gift of being rational, being made in the image of God is a method of restoration, of renewed creation for man, so that he may return to his place, that he may abide in the life of blessedness, fulfilling his purpose and in doing so praising God. For how is it that all creation blesses God other than by doing His word, performing the tasks which He created them to do. “Let every breath praise the name of the LORD”. Hence, the call for us to praise and exalt His name and give thanks to Him in the final stanza of this hymn. There are many other Patristic works that are suitable for this discussion, maybe even more so than what I’ve highlighted here, but these were the passages that came to mind, as I constantly remember studying this text with Fr. John Behr, and just beginning to understand, as if wetting my feet at the shore, the depth of what is to be rational.

As an aside, the liturgy of St. Gregory in the Coptic Rite has a similar theme… “You inscribed in me the image of Your authority. You have given me the gift of speech” (here using the Coptic word ⲥⲁϫⲓ which is the equivalent of the Greek λογος) amidst all the text regarding what Christ did for man, to which then the priests responds in the Institution, “I offer You, O my Master the symbols of my freedom. I write my works after/in keeping with Your words…”. It shares the idea that God gifts man this being rational, being in His image, and man in response offers back to God.

Now then, after all this, I arrive at what may be considered the epitome and controversey of my writing today—

Why is it that these changes to our texts can be made so quickly?

Why do suggested changes not undergo proper study? Who evaluates suggestions and what are their QUALIFICATIONS to do so?

On whose authority can these texts be altered? Is it an app developer, a priest, a bishop even?

What is the role of the Holy Synod in addressing these things, if any at all? How is it different in Egypt? In the diaspora?

Is there a system by which liturgical development/restoration can be implemented or even acknowledged?

What process must a text/rite go through in order to be adjusted if there is even need to do so?

How has the use of applications during liturgical worship affected our ability to understand our prayers? How has it affected our participation?

What has happened to our familiarity with the books of the Church and how to use them?

What makes these applications liturgical standards? Has convenience superseded understanding in our liturgical practice?

Do we as a community think before we proceed with changes? Do we count the cost so to speak?

What is the role of academic work in regards to our liturgical life, if any? And if so, are academics functioning in this capacity now? If not, what steps can be taken to further academic work in the liturgical space within the Church?

And many, many more concerns, and ideas, and questions, and conundrums…

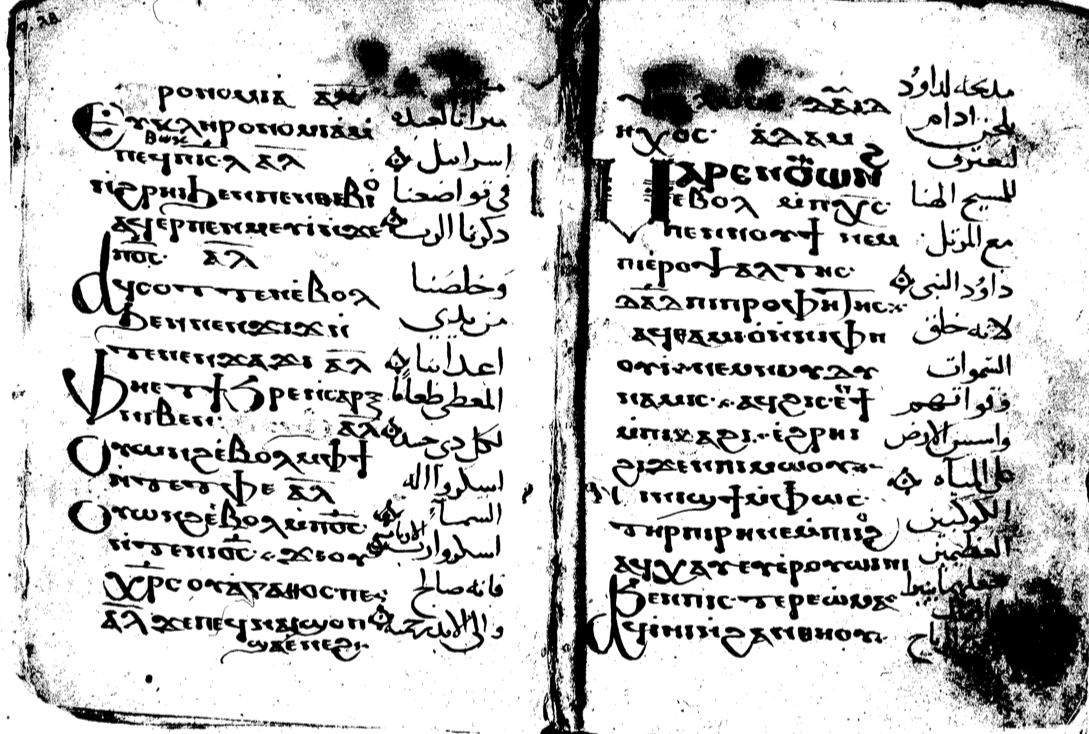

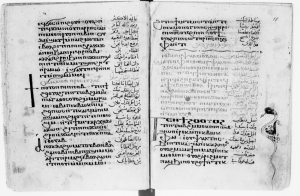

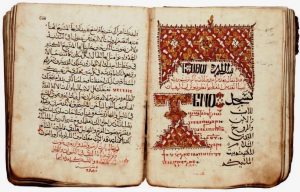

Bodl.Hunt.256 (1388 AD)

BNF 69 (14th cent.)

CVP.HMML.COPT 3 (14th cent.)

Vat.Copto.38 (1378 AD)

From the Second Qolo of Friday in the Shehimo (Book of Hours for the Syriac/Indian Orthodox Churches)