Over the years, I’ve received and asked the following question probably closer to a hundred times: “What does ‘As it was and shall be’ mean? What was and will be?”

What’s more interesting is the plethora of varied responses that I’ve heard. Here are just a few:

1. As the departed lived and died, so we will also live and die

2. As God led his people and kept them in the faith, so will he also do for us

3. Things never change (I.e. the human condition/situation)

4. The faith never changes

5. God never changes

A number of issues arise with these types of explanations:

1. They are not based on the text of the liturgy itself, but on personal interpretation, looking for a meaning to impose on the text, rather than extrapolating the meaning from the text itself (eisegesis vs. exegesis)

2. They are only based on the current placement of the text, particularly in the anaphora of St. Basil. Given that the hymn is prayed in all three anaphora (Basil, Cyril, and Gregory), the interpretation should be consistent amongst them, even when located in different sections. This should indicate that the subject of the text should be consistent. Yet, the above explanations only interpret the text based on its placement in St Basil’s anaphora and they do not hold up when compared across the other liturgies.

3. They are based on an improper version of the text of the original hymn and as a result an incorrect translation as well, into both Arabic and English.

So where do we go from here? This is going to be a bit in depth, so bear with me please.

Let’s first begin with the text of the hymn. What is most commonly used now is the following:

ⲱⲥ ⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ ⲕⲉ ⲉⲥⲧⲉ ⲉⲥⲧⲓⲛ ⲁⲡⲟ ⲅⲉⲛⲉⲁⲥ ⲕⲉ ⲡⲁⲛⲧⲁⲥ ⲧⲟⲩⲥ ⲉⲱⲛⲁⲥ ⲧⲱⲛ ⲉⲱⲛⲱⲛ ⲁⲙⲏⲛ

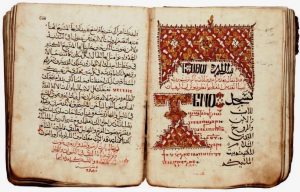

Would it interest you to know that this response is actually not the original text? Did you know that the cantors actually recorded the more authentic text in their renditions of Sts. Gregory and Cyril? Did you know that the officially ratified euchologion (“kholagy”) of the church has the original as the primary text unlike what we see today? Let’s compare:

ⲱⲥ ⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ ⲕⲉ ⲉⲥⲧⲓⲛ ⲕⲉ ⲉⲥⲧⲁⲓ ⲉⲓⲥ ⲅⲉⲛⲉⲁⲥ ⲅⲉⲛⲉⲱⲛ ⲕⲉ ⲉⲓⲥ ⲧⲟⲩⲥ ⲥⲩⲙⲡⲁⲛⲧⲁⲥ ⲁⲓⲱⲛⲁⲥ ⲧⲱⲛ ⲁⲓⲱⲛⲱⲛ ⲁⲙⲏⲛ

(Ώσπερ ην και έστιν και εσται εις γενεάς γενεών και εις τους συμπαντας αιώνας των αιώνων αμήν)

Here are the main differences:

1. Tense – the sequence in the original text is written as ⲏⲛ ⲕⲉ ⲉⲥⲧⲓⲛ ⲕⲉ ⲉⲥⲧⲁⲓ which means “was, and is, and shall be”. In the common text, it is written as ⲏⲛ ⲕⲉ ⲉⲥⲧⲁⲓ ⲉⲥⲧⲓⲛ which translates to “was, and shall be, is”.

2. Person – all three of these verbs are conjugated in the third person singular forms. In Greek, as is in Coptic, there is no distinction between the conjugations for third person masculine or third person neuter.

3. Structure – in the original text, “As … was, and is, and shall be unto generations of generations”—here the shall be fragment falls right into place with the remainder of the sentence, whereas in the common text, “As … was and shall be, from generation to generation…” or now as CR has it “As … was and shall be, [it is] from generation to generation…” has a sentence structure that moves back and forth from what was to what will be and back to what is now etc.

Of note, the latter response above (the older/primary text) is at least as old as the euchologion of St. Sarapion of Thmuis (4th century), though it isn’t necessarily used there as a hymn by the laity.

In his 2008 publication, “Al-Quddas Al-Ilahy: Sir Malakut Allah”, Fr. Athanasius Al-Maqary concludes that the response should not be translated “As it was…” but rather “As He was…”. For this he gives a number of reasonings:

1. That, in following with the rest of the anaphora, all the original congregation hymns/responses are glorifications of the Holy Trinity

2. That the structure of this portion of the liturgy has changed, separating into two pieces what is originally one segment. In its original placement, the hymn would fall after ϩⲓⲛⲁ ⲛⲉⲙ ϧⲉⲛ ⲫⲁⲓ not before it, and as a result the hymn is a praise of the Holy Trinity.

3. That the aorist third person ην is referring to He, as in God, not it, as in some other entity.

Though Al-Maqary draws logical conclusions here, I believe I have something humble to add to his contributions, and that this hymn (along with numerous other parts of our liturgy) focuses on the name of God. Let’s go back to the beginning—rather, let’s dive into the Scriptures.

Exodus 3:13 Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” 14 God said to Moses, “I AM WHO I AM.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel, ‘I AM has sent me to you.’” 15 God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel, ‘The LORD, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you’: this is my name for ever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations.

Let’s take a look at the what the text was before it was translated to English. Of course, the Scriptures (OT) were initially written in Hebrew, then translated to Greek (multiple times) and subsequently into other languages, of which, of the utmost importance is Coptic (not saying this because we’re Copts; in fact, I would think that any biblical scholar values the Coptic translation of the Scriptures—AKA LEARN YOUR MOTHER TONGUE). I will focus predominantly on the three times the name of God is identified here.

The first—“I AM WHO I AM”- the Hebrew אֶֽהְיֶ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֣ר אֶֽהְיֶ֖ה (’eh·yeh ’ă·šer ’eh·yeh) is in the first person and is a form of the verb to be. (This is not a coincidence; paraphrasing Robert Alter who says it best, “rivers of ink have been spilled writing about this name”. This is then translated into Greek as ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ Ὤν (“I AM THE ONE WHO IS” or “I AM HE WHO IS”). And finally, this also is taken up into the Coptic as ⲁⲛⲟⲕ ⲡⲉ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ (with the same meaning as the Greek). Note that the Greek uses a participle which is a verbal noun. The second—ὁ Ὤν or ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ is used here as a standalone, I AM or HE WHO IS, and we see these three letters often in the cross in surrounding Christ’s head in Orthodox iconography. And the third “The LORD” is the supremely interesting one. The Hebrew text uses the word •יְהוָ֞ה YHWH. For the Jews, this name over time was understood to be of the utmost holiness, and as a result, the Hebrews would not utter it. Instead, they used the vowel markers to alter its pronunciation to result in Adonai, meaning master/lord, so that no one would actually utter the name YHWH. In fact, the Hebrew language does not use the verb to be, and the Jewish people do not say the name YWHW to this very day (according to my Hebrew tutor). So by the time of the translation of the Scriptures into Greek or Coptic, the word YHWH was intoned as Adonai, which was translated then into Greek as κυριος and into Coptic as ⲡϭⲟⲓⲥ (B), ⲡϫⲟⲉⲓⲥ (S) which is abbreviated in Bohairic Coptic as ⲡ⳪︦.

Alright, well what does this have to do with ⲱⲥⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ? So many things ![]()

The earliest attestations to the hymn ⲱⲥⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ in the three Coptic Anaphora consistently place it after ϩⲓⲛⲁ ⲛⲉⲙ ϧⲉⲛ ⲫⲁⲓ. Let’s start with St Basil’s liturgy as an example.

Ⲛⲏ ⲙⲉⲛ ⲡ⳪︦ ⲙⲁⲙ̇ⲧⲟⲛ ⲛⲱⲟⲩ ϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲙⲁ ⲉⲧⲉⲙⲙⲁⲩ ⳾ ⲁⲛⲟⲛ ⲇⲉ ϩⲱⲛ ϧⲁ ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ϫⲱⲓⲗⲓ ⲙ̀ⲡⲁⲓⲙⲁ ⲁⲣⲉϩ ⲉⲣⲟⲛ ϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲉⲕⲛⲁϩϯ ⳾ ⲁⲣⲓϩⲙⲟⲧ ⲛⲁⲛ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉⲕϩⲓⲣⲏⲛⲏ ϣⲁ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⳾ ϭⲓⲙⲱⲓⲧ ϧⲁϫⲱⲛ ⲉϧⲟⲩⲛ ⲉⲧⲉⲕⲙⲉⲧⲟⲩⲣⲟ ⳾

Ϩⲓⲛⲁ ⲛⲉⲙ ϧⲉⲛ ⲫⲁⲓ ⳾ ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲫⲣⲏϯ ⲟⲛ ϧⲉⲛ ϩⲱⲃ ⲛⲓⲃⲉⲛ ⳾ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉϥϭⲓⲱⲟⲩ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉϥϭⲓⲥⲙⲟⲩ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉϥϭⲓⲥⲓ ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ⲡⲉⲕⲛⲓϣϯ ⲛ̀ⲣⲁⲛ | ⲉ︦ⲑ︦ⲩ︦ ϧⲉⲛ ϩⲱⲃ ⲛⲓⲃⲉⲛ | ⲉⲧⲧⲁⲓⲏⲟⲩⲧ | ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲉⲧⲥⲙⲁⲣⲱⲟⲩⲧ | ⲛⲉⲙ ⲓ︦ⲏ︦ⲥ︦ ⲡ︦ⲭ︦ⲥ︦ ⲡⲉⲕⲙⲉⲛⲣⲓⲧ ⲛ̀ϣⲏⲣⲓ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲡⲓⲡ︦ⲛ︦ⲁ︦ ⲉ︦ⲑ︦ⲩ︦ ⳾

Ⲱⲥ ⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ ⲕⲁⲓ ⲉⲥⲧⲓⲛ ⲕⲁⲓ ⲉⲥⲧⲁⲓ ⲉⲓⲥ ⲅⲉⲛⲉⲁⲥ ⲅⲉⲛⲉⲱⲛ ⲕⲁⲓ ⲉⲓⲥ ⲧⲟⲩⲥ ⲥⲩⲙⲡⲁⲛⲧⲁⲥ ⲁⲓⲱⲛⲁⲥ ⲧⲱⲛ ⲁⲓⲱⲛⲱⲛ ⲁⲙⲏⲛ ⳾

(Note that ϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲡⲁⲣⲁⲇⲓⲥⲟⲥ ⲛⲧⲉ ⲡⲟⲩⲛⲟϥ etc. is not included because it is not part of the original text, and this was also annotated in the euchologion of 1902)

Priest: Those, O LORD, repose them in that place; and we, too, who are sojourners in this place, keep us in/by Your faith (faith of/in You), grant us Your peace unto the end (always), and lead the way for us into Your kingdom—that in this, likewise in all, Your great, all-holy, honored, and blessed Name be glorified, praised, and exalted with Your beloved Son and the Holy Spirit.

People: As He-Was and Is and Shall-Be unto generations of generations and unto the ages of all ages. Amen.

Priest: Peace be unto all.

People: And with your spirit.

| Ⲡⲁⲗⲓⲛ ⲟⲛ ⲙⲁⲣⲉⲛϣⲉⲡϩⲙⲟⲧ ⲛ̀ⲧⲟⲧϥ ⲙ̀ⲫⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲡⲓⲡⲁⲛⲧⲟⲕⲣⲁⲧⲱⲣ ⳾ ⲫⲓⲱⲧ ⲙ̀ⲡⲉⲛ⳪ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲡⲉⲛⲛⲟⲩϯ ⳾ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲡⲉⲛⲥⲱⲧⲏⲣ ⲓ︦ⲏ︦ⲥ︦ ⲡ︦ⲭ︦ⲥ︦ ⳾ Ϫⲉ ⲁϥⲑⲣⲉⲛⲉⲣⲡⲉⲙⲡϣⲁ ⲟⲛ ϯⲛⲟⲩ ⳾ ⲉⲟϩⲓ ⲉⲣⲁⲧⲉⲛ ϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲁⲓⲙⲁ ⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲫⲁⲓ ⳾ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲉϥⲁⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲉⲛϫⲓϫ ⲉⲡϣⲱⲓ ⳾ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲉϣⲉⲙϣⲓ ⲙ̀ⲡⲉϥⲣⲁⲛ ⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⳾ Ⲛⲑⲟϥ ⲟⲛ ⲙⲁⲣⲉⲛϯϩⲟ ⲉⲣⲟϥ ⳾ ϩⲟⲡⲱⲥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉϥⲁⲓⲧⲉⲛ ⲛ̀ⲉⲙⲡϣⲁ ⳾ ⲛ̀ϯⲙⲉⲧϣⲫⲏⲣ ⲛⲉⲙ ϯⲙⲉⲧⲁⲗⲩⲙⲯⲓⲥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲛⲉϥⲙⲩⲥⲧⲏⲣⲓⲟⲛ ⲛ̀ⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲁⲑⲙⲟⲩ ⳾ Ⲡⲓⲥⲱⲙⲁ ⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⳾ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲡⲓⲥⲛⲟϥ ⲉⲧⲧⲁⲓⲏⲟⲩⲧ ⳾ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲡⲉϥⲭⲣⲓⲥⲧⲟⲥ ⳾ ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ⲡⲓⲡⲁⲛⲧⲟⲕⲣⲁⲧⲱⲣ ⳾ ⲡ⳪ ⲡⲉⲛⲛⲟⲩϯ ⳾ | Again, let us give thanks to God, the Pantocrator, Father of our Lord, God, and Savior, Jesus Christ, for He has made us worthy, now, to stand even in this holy place, to lift up our hands, and to serve His holy name. Let us also entreat Him that He make us worthy of the communion and partaking of His divine and immortal mysteries: the holy body and the precious blood of His Christ, the Pantocrator, the LORD, our God. |

Let’s dig a little deeper now! The Coptic Anaphora of St Basil can be split into two major sections, both beginning with thanksgiving. The first is “The LORD be with you all…Let us give thanks to the LORD” and the second is “Again, let us give thanks.” So here, the first section concludes with a glorification of the name of our God—that in all things Your name may be glorified. And the people thus respond with the divine name, He was and is and shall be, i.e. He Who Is. That’s not all…what does this have to do with the generations? Look back to Exodus 3:15—“This is My name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations.” The focus of this entire segment of the liturgy is the doxology on the name of God. And now when we begin again, we begin with the name of our God—“and to serve His holy name”.

Let’s throw in some more details! In the early Christian Church, a great emphasis was placed on identifying the God whom the Christians worshipped; they had to clearly state that this Jesus Christ is himself YHWH, the One Who Is, the God of the OT that they were awaiting. Also, Jesus Christ our LORD, revealed to us that He is the image of God the Father and sent to us His Spirit. Thus, Christian liturgy has an extremely heavy emphasis on identifying and describing the attributes of the God whom worship is directed to. Now then, we said that the name of God is given as either ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ or ⲡ⳪︦, or reffered to by using the ⲁⲛⲟⲕ ⲡⲉ in the Coptic language, and while we use those words so frequently, oftentimes translation or lack of context, hinder us from understanding the meaning.

In the Anaphora of St. Basil, we begin with:

| Ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ⲫⲛⲏⲃ ⲡ⳪︦ ⲫⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ϯⲙⲉⲑⲙⲏⲓ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ϧⲁϫⲱⲟⲩ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓⲉⲛⲉϩ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲟⲩⲣⲟ ϣⲁ ⲉⲛⲉϩ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ϧⲉⲛ ⲛⲏⲉⲧϭⲟⲥⲓ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲉⲧϫⲟⲩϣⲧ ⲉϫⲉⲛ ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲑⲉⲃⲓⲏⲟⲩⲧ ⲫⲏⲉⲧⲁϥⲑⲁⲙⲓⲟ ⲛ̀ⲧⲫⲉ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲡⲕⲁϩⲓ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲉ ⲛ̀ϧⲏⲧⲟⲩ ⲧⲏⲣⲟⲩ ⲫⲓⲱⲧ ⲙ̀ⲡⲉⲛ⳪︦ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲡⲉⲛⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲡⲉⲛⲥⲱⲧⲏⲣ ⲓ︦ⲏ︦ⲥ︦ ⲡ︦ⲭ︦ⲥ︦ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲉⲧⲁⲕⲑⲁⲙⲓⲟ ⲙ̀ⲡⲧⲏⲣϥ ⲉⲃⲟⲗϩⲓⲧⲟⲧϥ ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲩⲛⲁⲩ ⲉⲣⲱⲟⲩ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲉ ⲛ̀ⲥⲉⲛⲁⲩ ⲉⲣⲱⲟⲩ ⲁⲛ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϩⲉⲙⲥⲓ ϩⲓϫⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲑⲣⲟⲛⲟⲥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲡⲉϥⲱⲟⲩ ⲫⲏⲉⲧⲟⲩⲱϣⲧ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟϥ ϩⲓⲧⲉⲛ ϫⲟⲙ ⲛⲓⲃⲉⲛ ⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ | O You, He Who Is, Master, LORD, God of Truth, He Who Is before the ages and reigns forever He Who Is in the highest and looks upon the lowly He Who has created the heaven, the earth, the sea and all that is therein, Father of our LORD, God, and Savior, Jesus Christ—He by whom/whose hand You have created all things, the visible and the invisible, He Who sits upon the throne of His glory, He Who is worshipped by every holy host/power, |

The current English translation most parishes use now is “O You, THE BEING”. And while the intent of this being in all caps was to indicate the Divine Name, to our modern sensibilities it really is heard as “O You the thing over there” which of course is not the intent whatsoever. You may say, “Well, how is ‘O You, He Who Is’ any better?” And to that I would say, the repetition of the word ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ or He Who Is clearly is not haphazard, and is meant to be poetic in order to apply to all three statements in the same manner. Instead of The BEING, and He who is, and He who dwells, it is the repetition of the divine name.

Furthermore, the anaphora here identifies that God, the Father, is Himself YHWH, the One Who Is. The Anaphora of St Cyril, also speaking of the Father, says, ⲕⲉ ⲅⲁⲣ ⲁⲗⲏⲑⲱⲥ ϥⲉⲙⲡϣⲁ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲟⲩⲇⲓⲕⲉⲟⲛ ⲡⲉ ⳾ ϥⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲇⲉ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ϥⲉⲣⲡⲣⲉⲡⲓ ⳾ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ϥⲉⲣⲛⲟϥⲣⲓ ⳾ ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲉⲛⲟⲩⲛ ⲙ̀ⲯⲩⲭⲏ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲛⲉⲛⲥⲱⲙⲁ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲛⲉⲛⲡ︦ⲛ︦ⲁ︦ ⳾ Ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ⲫⲛⲏⲃ ⲡ⳪︦ ⲫϯ ⲫⲓⲱⲧ ⳾ “For truly, it is worthy and right, holy and befitting, and good for our souls, bodies, and spirits—O You, Who-Is, Master, Lord God, the Father, the Pantocrator…to praise You, hymn You, serve You, worship You, glorify You, and confess to You, night and day…”. If we turn to the Anaphora of St. Gregory, we see the phrase ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ⲫⲛⲏⲃ ⲡ⳪︦ ⲫϯ ⲛ̀ⲧⲁⲫⲙⲏⲓ ⲉⲃⲟⲗϧⲉⲛ ⲟⲩⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲛ̀ⲧⲁⲫⲙⲏⲓ, O You, He Who Is, Master, LORD, true God of true God—who is the true God of true God other than the LORD Jesus Christ. Therefore, in just these few statements the Coptic liturgical tradition proclaims that Jesus Christ is YHWH, and later in the same piece, speaks of the Holy Spirit as well in the same manner. Again, in the Anaphora of St Gregory, we see ⲛⲑⲟⲕ [ⲡⲉ] ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ⲛ̀ⲥⲏⲟⲩ ⲛⲓⲃⲉⲛ ⲁⲕⲓ ⲛⲁⲛ ϩⲓϫⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲕⲁϩⲓ ⲁⲕⲓ ⲉⲑⲙⲏⲧⲣⲁ ⲛ̀ϯⲡⲁⲣⲑⲉⲛⲟⲥ — “You, He Who Is at all times, have come to us on the earth. You have come to the womb of the Virgin.” So then, our three anaphora begin by speaking of the name of our God, identifying Him according to what He has revealed to us through the advent of His Son, which we perform liturgically by the dwelling and work of the Holy Spirit. AND this is all aside from the fact that the beginning of each of the anaphora start with “The LORD be with you all” or “The love of God the Father, the grace of the Only Begotten Son, our LORD, and the communion and gift of the Holy Spirit be with you all” clearly identifying the one God.

Using this is a sort of template, if we look to the hymn ⲱⲥⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ in the other two anaphora, we should find a similar theme.

In St. Gregory, the hymn initially came after ϩⲓⲛⲁ ⲛⲉⲙ ϧⲉⲛ ⲫⲁⲓ as it did in St. Basil with the exception that St. Gregory, because it speaks to the Son of God, has one difference in the conclusion of the piece; instead of ⲛⲉⲙ ⲡⲉⲕⲙⲉⲛⲣⲓⲧ ⲛ̀ϣⲏⲣⲓ, it says, ⲛⲉⲙ ⲡⲉⲕⲓⲱⲧ ⲛ̀ⲁⲅⲁⲑⲟⲥ. The tricky and confusing one, that never made sense to me (and I’m sure to some of you) all my life, was the placement of the response in St Cyril’s liturgy. For the other two anaphora, the music and the placement of the hymn is familiar, so it’s easy on the ears. However, in St. Cyril’s, it is a bit jarring as the tunes are not as well known, and the liturgical structure itself is unfamiliar to us now (though it is the authentically Alexandrian anaphora ![]() ) So let’s take a look at what precedes ⲱⲥⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ in St. Cyril’s Anaphora.

) So let’s take a look at what precedes ⲱⲥⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ in St. Cyril’s Anaphora.

Though it still is placed directly prior to the conclusion of the first segment of the liturgy, and prior to “Again, let us give thanks”, what precedes ⲱⲥ ⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ in this anaphora has nothing at all to do with the departed or our repose etc. The text in the liturgy of Mark reads as follows:

“And send down from Your holy heights, and from Your prepared dwelling, and Your unimpeded bosom, and from the throne of the kingdom of Your glory, the Paraclete, Your Holy Spirit—He Who Is in a hypostasis, the immutable, unchangeable, LORD, Giver of Life, He who spoke in the law and the prophets and the apostles, He Who Is in every place, and fills every place, and yet no place can contain, and who of His own authority, by Your pleasure, works purity on/in those whom He loves, not in servitude, the simple/single in His nature, He who is manifold in his works, the fountain of divine gifts/graces, He who is of one essence with You, He who is proceeding/coming from You, the partner of the throne of the kingdom of Your glory, with Your Only Begotten Son, our LORD, our God, and our Savior, and King of us all, Jesus Christ—upon us, we Your servants, and upon these precious gifts which have been set before You, upon this bread and this cup, that they may be sanctified and changed…that they may be unto all of us, we who partake of them, a faith without examination, a love without hypocrisy, a perfect/complete patience/endurance, a firm hope, a faith, a watchfulness, a health, a joy, a renewal of the soul, and the body, and the Spirit, A GLORY TO YOUR HOLY NAME, a fellowship in the blessedness of eternal life and incorruption and a forgiveness of sins, in order that in this—so also in all things…” (In today’s practice the last segment, “in order that in this…” comes after the response ⲱⲥ ⲡⲉⲣ ⲏⲛ (as it does in the modern practice of all three anaphora) but as we said initially it came first.)

So you can see from these beautiful prayers, that the focus of this hymn and these entire segments of the liturgy centers around the glorification of the holy divine name of our God, YHWH, the One Who Is, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

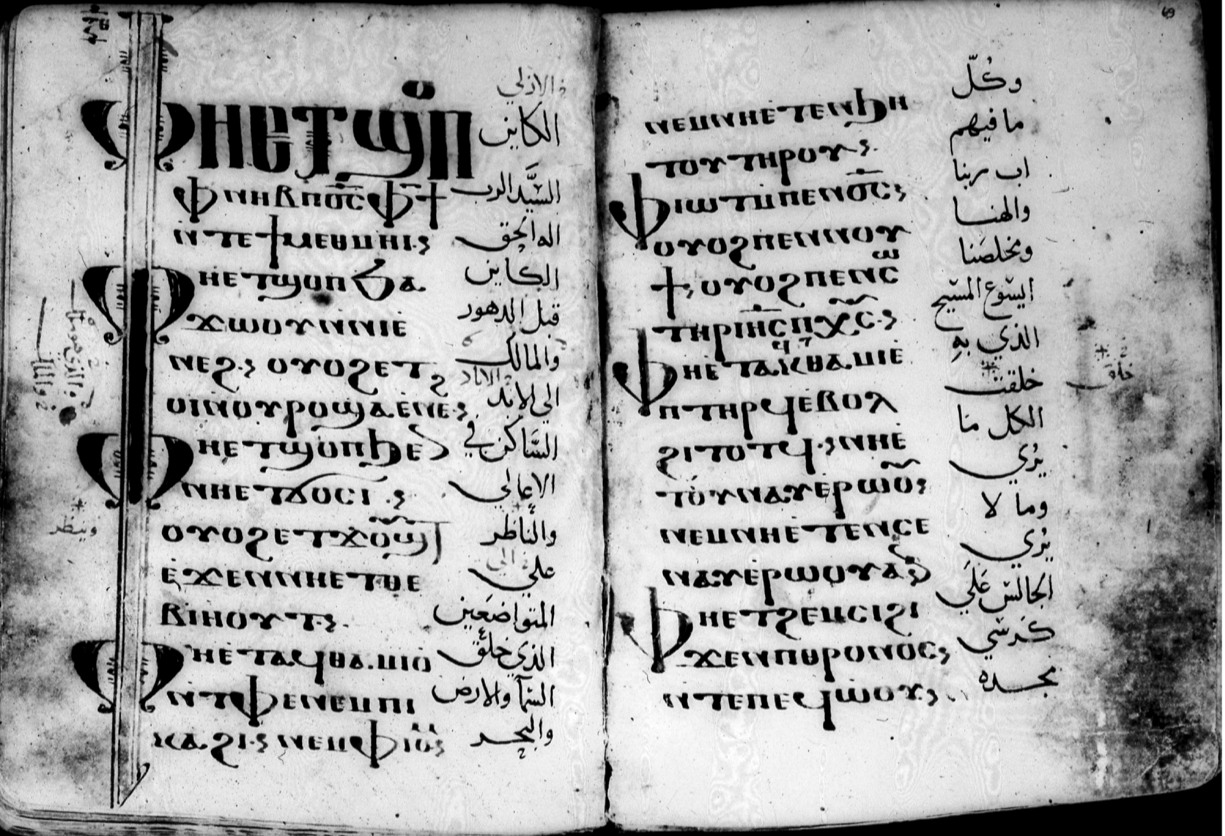

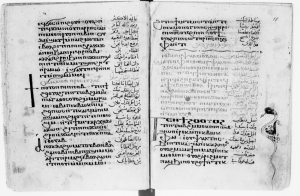

Someone may ask me, “how in the world did it get so different?” or “how do you know that you’re correct?”. To them I will answer, we have documentation of this hymn in our liturgics from as early as the 13th century (though the text itself predates that by many centuries as I previously stated). It has been translated into Arabic many times over those years. These Arabic translations, while they may not be exact, explain to us the understanding of the Copts and how they interpreted the response throughout the centuries. I’ve seen a range of translations which include:

1. انت الازلي (Vat.Copt.17 – 1288 AD, and others) “You are the Eternal One”

2. انت كنت (Bodl.Hunt.256 – 1388 AD, and others) “You were and are and will be”

3. الذي لم يزل (Vat.Copt.27 – 1484 AD, and others) “He who was”

In addition to Louis Bouyer’s translation of the text in the euchologion of Serapion, these translations throughout the Middle Ages, give us a glimpse into the mind of the Copts who prayed the hymn as a congregation response. They understood the text to be speaking of YHWH.

In terms of how we got to this point, I have only seen one manuscript so far that includes anything similar to the modern day text of the response. In the catalogue of the manuscript (BL.OR.5282), it says that the text was “written for the church of the Virgin in Harat Zuwailah, by one of the priest’s pupils, aged eleven, in A.D. 1872.” My assumption would be that at that time the text of this response was available, or that this pupil made some errors as is evident by the remainder of the manuscript. It is also fascinating that this manuscript also includes the additions into ⲛⲏ ⲙⲉⲛ ⲡ⳪︦ that have now become part of every book and app text, while it was never present in any medieval text. Read into that as you wish ![]()

There are a number of other hymns that have secretly, or rather not so secretly, been playing on this concept of the name of God. During Kiahk, many parishes (though this is now dwindling because of the TERRIBLE practice of singing random melodies from the midnight office) chant ϥⲉⲙⲡϣⲁ ⲅⲁⲣ:

| Ϥⲉⲙⲡϣⲁ ⲅⲁⲣ ϧⲉⲛ ⲟⲩⲙⲉⲑⲙⲏⲓ ⳾ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲟⲩⲇⲓⲕⲉⲟⲛ ⲡⲉ ⳾ ⲉⲑⲣⲉⲛϩⲱⲥ ⲉⲫϯ ⲛ̀ⲧⲁⲫⲙⲏⲓ ⳾ ⲡ⳪︦ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ϧⲉⲛ ⲧⲫⲉ ⳾ | For, it is truly • worthy and just • that we praise the true God, • the LORD, He-Who-Is in heaven. • |

| Ⲡⲉϥⲣⲁⲛ ϩⲟⲗϫ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ϥⲥⲙⲁⲣⲱⲟⲩⲧ ⳾ ϧⲉⲛ ⲣⲱⲟⲩ ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⳾ ⲉⲧⲉ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲡⲉ ⲫⲓⲱⲧ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲡϣⲏⲣⲓ ⳾ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲡⲓⲡ︦ⲛ︦ⲁ︦ ⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⳾ | His name is sweet and blessed • in the mouths of the saints, • name the Father, Son • and Holy Spirit. • |

While we may not have noticed before, the hymn is clearly beginning by connecting LORD, He Who IS, with Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

And that’s not all. The fact that we have the daily psali on the name of the LORD Jesus Christ and consistently say ⲡⲁ⳪︦ ⲓ︦ⲏ︦ⲥ︦ ⲡ︦ⲭ︦ⲥ︦ is no simple matter! The use of the word “lord” and name “LORD” has multiple layers of meaning. We are not only calling to Him as our lord and master, but as YHWH, the LORD. And the concept that our God is LORD, He is the ONE WHO IS, carries a depth that is indescribable; from Him we along with the rest of creation draw our entire being, and the calling upon His Divine Name invokes His presence among us, within us, and as sons of the Father we petition Him in each liturgy to “have mercy on us all for the sake of His holy name which is called upon us”.

And one more fun little discovery! In ⲁⲣⲓⲯⲁⲗⲓⲛ (everyone’s favorite chant, I’m sure) there is a verse towards the end that everyone thinks makes lots of sense. Unfortunately, yes we’ve been missing a huge point in it the entire time.

ⲫⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲡⲁⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲉⲅⲱ ⳾ ⲡⲉ ⲡⲉⲛⲣⲉϥⲥⲱϯ ⲉⲕ ⲧⲱⲛ ⲁⲅⲱ ⳾ ⲥⲉⲇⲣⲁⲕ ⲙⲓⲥⲁⲕ ⲁⲃⲇⲉⲛⲁⲅⲱ ⳾ ϩⲱⲥ ⲉⲣⲟϥ ⲁⲣⲓϩⲟⲩⲟ ϭⲁⲥϥ

Most of us now see ⲡⲉⲧⲉⲛⲣⲉϥⲥⲱϯ in our modern texts but examining the older texts in the psalmodies provided me with the above text. What Sarkis is doing here is quite interesting! He is using ⲉⲅⲱ from εγω ειμι (Greek I AM) and the ⲡⲉ from ⲁⲛⲟⲕ ⲡⲉ (Coptic I AM) and fusing them into one ⲉⲅⲱ ⲡⲉ in order to mention the name of God. The PROOF of this is the old arabic translation, الله الهي انا هو … “God, my God, I AM, • is our savior from danger, • O Shedrach, Mishach, and Abednego”

Now, after writing all this, I have to put all the pictures together, so here I will stop, and wish you all a very Merry Christmas for those of us celebrating on the old calendar, and I pray that YHWH, our LORD, HE WHO IS, makes His dwelling in us and is incarnate in each and every one of us that we may also be His presence in the world. Pray for me!

Oh! I forgot one more thing—we see this again in the “Graciously accord, O Lord”

“Befitting of You is blessing! Becoming of You is praise! Belonging to You is glory, O Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, He-Who-Is (ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ), from the beginning, now and unto the age of all ages! Amen.

Please, everyone, as much as is possible, at least glance at the Coptic text of our liturgical prayers. Things will finally connect. I beg you, learn the language of your ancestors and immerse yourself in the manner in which they worshipped our God. It has saved so many.