When you hear the phrase, “The holies [are] for the holies,” what comes to your mind? For me, my memory takes me straight to the ending of the Coptic Eucharistic liturgy, just prior to the confession. But, would it interest you to know, that this theme, this motion, is present all throughout the liturgy? Today, I would like to analyze this motif with you, particularly in the Coptic Anaphora of St. Basil.

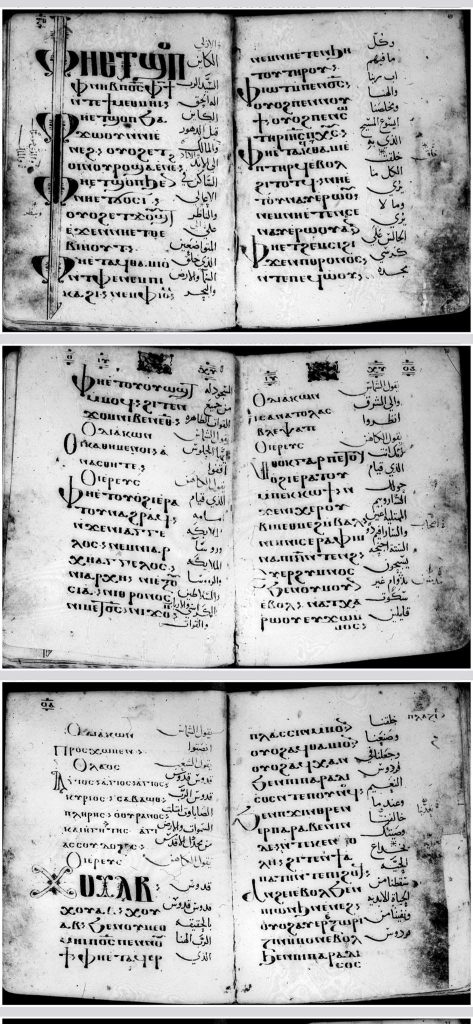

At the opening of the Anaphora, the priest prays:

O You, He-Who-Is, Master, LORD, God of Truth,

He-Who-Is before the ages and reigns forever,

He-Who-Is in the highest and looks upon the lowly,

He who has created the heaven, the earth, the sea and all that is therein,

Father of our LORD, God, and Savior, Jesus Christ—He by whom (lit. whose hand)You have created all things, the visible and the invisible,

He who sits upon the throne of His glory,

He who is worshipped by every holy host,

He before whom stand the angels, the archangels, the principalities, the authorities, the thrones, the dominions, and the powers,

You are He around whom stand the cherubim, full of eyes, and the seraphim of the six wings, hymning continuously, without ceasing, saying,

At this point, the fullness of the Church joins the cherubim and seraphim in the vision of Isaiah, and we cry out:

“Holy, holy, holy, LORD of hosts. Heaven and earth are full of your holy glory.”

Let’s stop here for just a moment and briefly discuss the commands of the deacon: “You who are seated, stand” and “Look towards the East”. When taken literally alone, these two responses make very little sense. Just a few moments beforehand, the deacon had already told us to stand five or six different ways (In Basil, “with trembling”, in Gregory, “peacefully, reverently, eagerly” etc.) and he tells us to look towards the east in the same vein. So why would he need to say these things again, just a few minutes later, especially since there hasn’t been much of a chance for us to sit down and look in another direction?

The answer is more likely that these commands are meant to be understood eschatologically or ontologically—the standing here, ⲁⲛⲁⲥⲑⲏⲧⲉ, is the same verb for rising (like resurrection, ⲁⲛⲁⲥⲧⲁⲥⲓⲥ) and the entire command, per our manuscript tradition is replaced with, “Lord have mercy” during the Holy Fifty as a means of participation in Christ’s resurrection. This would mean that the intent of the command is more in line with a context of rising from death, that those who are seated [in the shadow of death] (Isaiah 9) should arise. In like manner, looking towards the East places us in the vision of Ezekiel, where God is seen coming forth from the Eastern Gate while it remains shut; the East is where the Church faces awaiting the coming of the LORD Jesus Christ, the Sun of Righteousness. Thus, this command of the deacon directs our attention to the presence of the LORD, and moves our focus towards an eschatological view of His coming; hence, we actively join with the heavenly hosts proclaiming, “Holy…”

It is at this point, that the priest should be signing the three crosses—one on himself, one on his concelebrant, and the third on the laity. Though the priest now chants three ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ (in the tune of the ⲁⲙⲏⲛ from ⲉⲓⲥ ⲡⲁⲧⲏⲣ), these three ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ are not attested to in our early euchologia. The three ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ that the priest originally signed the cross in were the three that are chanted by the people in ϫⲉ ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲅ︦ ⲕⲩⲣⲓⲟⲥ ⲥⲁⲃⲁⲱⲑ. In addition, the tune that is currently chanted for these three inserted ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ is completely outside the tune of the Basilian Anaphora.

Now then, the priest begins ⲭⲟⲩⲁⲃ which reads,

“Holy, holy, holy, indeed, O LORD, our God, He who formed us and created us and placed us in the paradise of joy.

In our disobeying/transgressing Your commandments, through the deceit of the serpent, we fell from the eternal life and were exiled from the paradise of joy. You abandoned us not to the end, but have visited us continuously through Your holy prophets, and in the end of the days (fullness of time?), You revealed Yourself to us—we who sit in the darkness and the shadow of death—by the life-giving manifestation of Your Only-Begotten Son, our LORD, God, and Savior, Jesus Christ, He who of the Holy Spirit and of the holy Virgin Mary took flesh; He became man and taught us the paths of [the] salvation, and having granted us the birth from on high through water and Spirit, He made us unto Himself an assembly and made us holy (ⲁϥⲑⲣⲉⲛϣⲱⲡⲓ ⲉⲛⲟⲩⲁⲃ) by Your Holy Spirit…”

It is here that I would suggest is the first movement of holies for the holies: we have identified the LORD our God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, exegeted Him as the subject of the theophanies in Scripture, and have ascribed Him the holiness due to Him, which He then gives to us.

Moving forward, our next stop is in the now (unfortunately) inaudible prayer of the Epiclesis:

“Therefore, also, remembering (lit. doing/enacting the remembrance) of His (Christ’s) holy passions, His resurrection from the dead, His ascension to the heavens, His sitting at Your right hand, O Father, and His second advent, coming from the heavens, awesome and fully of glory, we offer You (Father) Your gifts from that which is Yours, for every condition/thing, concerning every condition, and in every condition,

…

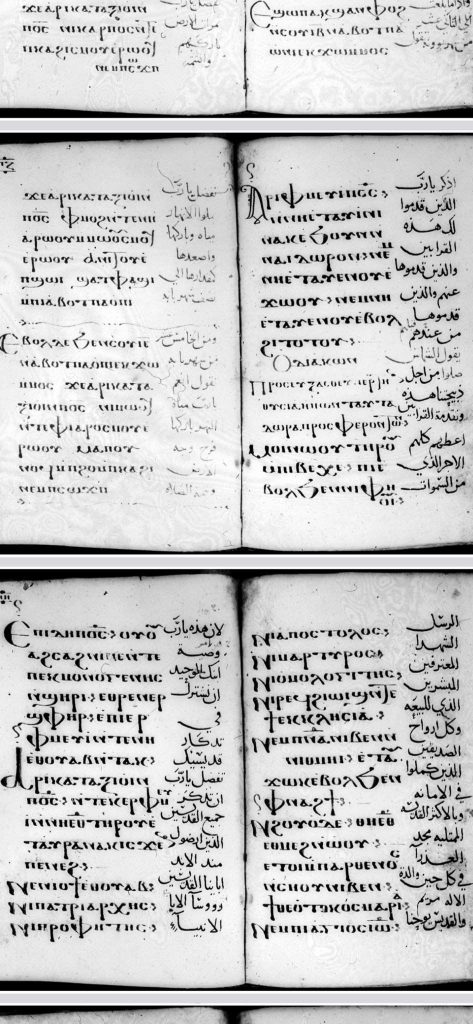

and we ask You, O LORD our God, we Your sinful and unworthy servants—we worship You by the pleasure of Your goodness—that Your Holy Spirit descend upon us, and upon these gifts set forth, and that He purify them, change/move them, and manifest them as holies for Your holies (ⲉⲩⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲛⲧⲉ ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲛⲧⲁⲕ)…and this bread—that He (Holy Spirit) makes it into His (Christ’s) holy body…and this cup also—the precious blood of His new covenant…given for the remission of sins, and eternal life to those who partake of Him/it.”

As we can see from this beautiful prayer, the primary focus of our liturgy is the movement of

the holies for the holies, our sanctification along with the that of the gifts into the Body and Blood of our LORD. Please also notice the specific Coptic verbiage ⲉⲩⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲛⲧⲉ ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲛⲧⲁⲕ as it is going to play a major role in the rest of this piece.

The priests will then continue,

“Make us all worthy, O our Master, to partake of Your holies (ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲛⲧⲁⲕ), as a purification for our souls, bodies, and spirits, that we may become one body and one spirit, and find a share and an inheritance with all Your saints (ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲛⲧⲁⲕ) who have pleased You since the beginning (lit. from the age).”

Once again, we see a clear movement from the holies (the gifts set forth and transformed) to us, and partaking of them we share in the inheritance of the holies, the saints!

Now, here’s the kicker ![]()

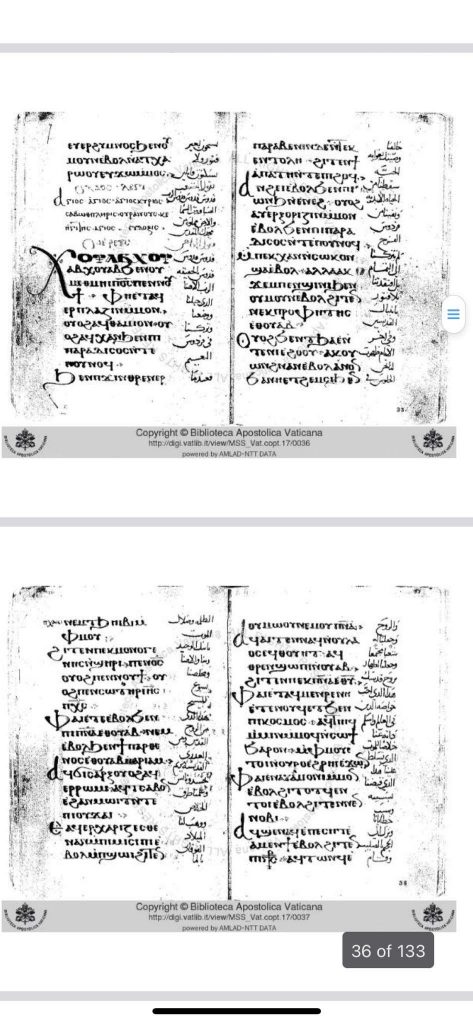

In the Anaphora of St Basil, and that of St Gregory, the structure of the following segment in the liturgy is always as follows:

1. Introductory segment of litany beginning with “Remember, O LORD” (ⲁⲣⲓⲫⲙⲉⲩⲓ ⲡ⳪︦) or “Vouchsafe/Graciously accord, O LORD” (ⲁⲣⲓⲕⲁⲧⲁⲝⲓⲟⲓⲛ ⲡ⳪︦).

2. A command from the deacon to the people to pray for the topic/subject introduced by the priest with some additional information.

3. The laity respond with, “Lord have mercy”

4. The continuation of the aforementioned litany which also functions as a transition into the subsequent prayer as well.

An older order of the Anaphora of Mark/Cyril indicates to us that structure I outlined above varies from what the Alexandrian tradition initially practiced:

1. Command of the Deacon

2. Complete litany by the Priest

3. Lord have mercy

In any case, in the Basilian and Gregorian style, the litanies or intercessory prayers of the priest function as an entire piece rather than separate prayers. If the interjections of the deacon and congregation are placed on the side for a moment, this very clear. As an example,

“Remember, O LORD, the peace of Your one, holy, Catholic and apostolic Church,

this which You have acquired to Yourself with the precious blood of Your Christ; keep her in peace with all the orthodox bishops in her.

Foremost,

Remember, O LORD, our honored father, the high priest, Pope Abba Tawadros II, and his partner…

and those who rightly divide the word of truth with him, grant them unto Your holy Church to shepherd Your flock in peace.

Remember, O LORD, the orthodox hegumens, priests, and deacons…”

So you can see these are contiguous prayers that connect to each other as if in one thought.

So, with this structure in mind, where is the continuation of the prayer for the oblations?

In modern practice, the prayer begins,

“Priest: Remember, O LORD, those who have brought to You these gifts, those on whose behalf they’ve been brought, and those by whom they have been brought. Give them all the heavenly reward.

Deacon: Pray for these holy and precious gifts, our sacrifices, and those who bring them.

People: Lord, have mercy.

And then we supposedly begin something called the “Commemoration of Saints”. Technically, there’s no such thing.

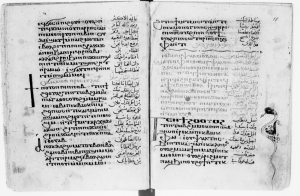

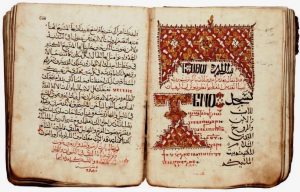

In our early manuscripts, there are no titles at all for any of these segments in the liturgy. In fact, even in the officially ratified 1902 euchologion, these segments are not separated from one another or given any titles. This partitioning is a recent innovation that has conditioned our minds to think a certain way, but it’s not the way that our ancestors understood their liturgy. In fact, the English translation “Commemoration of Saints” is not remotely close to the Arabic المجمع which is literally, “The Synod”—a title which is seen predominantly in psalmody manuscripts and not in the euchologion.

So, ignoring the modern titles and segmentation, let’s look at this section again.

“Remember, O LORD, those who have brought to You these gifts, those on whose behalf they’ve been brought, and those by whom they have been brought.

Give them all the heavenly reward as this, O LORD, is the command of Your Only Begotten Son: (ⲉⲑⲣⲉⲛⲉⲣϣⲫⲏⲣ ⲉⲡⲓⲉⲣⲫⲙⲉⲩⲓ ⲛⲧⲉ ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲛⲧⲁⲕ)

Currently, this last line is line is translated as “that we share in the commemoration of Your saints” but this is inaccurate and is biased because of the segmentation and imposed titles as I mentioned. Furthermore, we often asked and were asked this question as children: “When did Christ command us to remember the saints?” And it even became a point of contention between Orthodox and Protestant ideologies in Egypt—the Orthodox claiming that the liturgy tells us that Christ commanded it, and the Protestant saying that the Bible doesn’t mention it, therefore it is untrue. The Orthodox then need to figure out a response and so they make claims such as, “the LORD said that what the woman did when she anointed his feet will be told as a memorial of her” and that’s what intended in this segment. But this explanation is very weak given that the woman is not mentioned at all in the coming litany and this is not the focus of the Anaphora at any point.

The truth lies in the Coptic ![]() The Coptic of that last line literally translates to:

The Coptic of that last line literally translates to:

“that we participate/share/partake of the remembrance of Your holies. The beginning of what is now the “commemoration of saints” is actually the concluding segment of the litany of the oblations. And the proof is as follows:

A ) There is a link between the ⲉⲣⲫⲙⲉⲩⲓ here in this segment and in the Institution. “This do in REMEMBRANCE of me.” (ⲫⲁⲓ ⲁⲣⲓⲧϥ ⲉⲡⲁⲈⲢⲪⲘⲈⲨⲒ) This is the command that we do the remembrance of our LORD, that we constitute His body in the assembly and partake of His flesh and blood by means of the gifts.

B ) The litany itself in our manuscripts is not split up in the current place. Rather than “give them all the heavenly reward” being placed before the command of the deacon, our old texts include it afterwards so the prayer would look like this:

“Remember, O LORD, those who have brought to You these gifts, those on whose behalf they’ve been brought, and those by whom they have been brought.

Deacon: …

People: …

Priest: Give them all the heavenly reward, as this, O LORD, is the command…”

And in the same way that the previous litanies connected to one another, these two prayers do also.

“…that we share in the remembrance of Your holies.

Graciously accord, O LORD, to remember all the holies/saints who have pleased you since the beginning…”

Of note, the earliest extant Bohairic euchologion places the deacon command ⲛⲏ ⲉⲧⲱϣ between ⲉⲡⲉⲓⲇⲏ and ⲁⲣⲓⲕⲁⲧⲁⲝⲓⲟⲓⲛ. Additionally, when we remove the titles and segmentation, we see the congruence of this litany in both St Basil and St Gregory anaphora in that it begins with ⲁⲣⲓⲕⲁⲧⲁⲝⲓⲟⲓⲛ in both.

C ) Here, again, we see the movement mimicking previous sections, from the holies (gifts) to the holies (saints) and our participation in/share with them. This concept also gives a definitive answer to the notion that Christ didn’t command us to remember the saints—the LORD commanded us to constitute His body in the establishment of the Eucharistic mystery. We are His one body, both the saints who have passed from the earthly life and the saints who are present with us—the same body, the ONE CHURCH (side note: not divided into the struggling and victorious). In the liturgical gathering, we supersede space and time, and enter into the mysteries of the presence of God, partaking in His holiness.

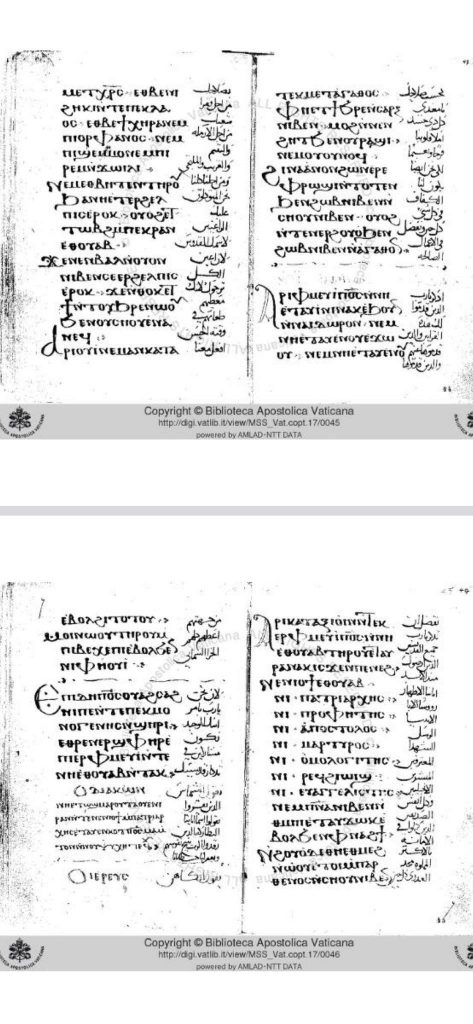

Moving along, let’s take a look at the latter portion of the standard fraction prayer in Basil,

“God, You who have sanctified (ⲉⲣⲁⲅⲓⲁⲍⲓⲛ) these very gifts set forth through the descent of Your Holy Spirit upon them, and have purified them (ⲁⲕⲧⲟⲩⲃⲱⲟⲩ),

purify us (ⲙⲁⲧⲟⲩⲃⲟⲛ)also, O our Master, from our sins, the hidden and the manifest, and every thought which pleases not Your goodness, O Lover of Man, let it be far from us;

purify our souls, and our bodies, and our spirits, and our hearts, and our eyes, and our understandings, and our thoughts, and our consciences,

so that with a pure/holy heart (ⲟⲩϩⲏⲧ ⲉϥⲟⲩⲁⲃ), and an enlightened soul, an unashamed face/countenance, a faith unfeigned, a perfect love, and a firm hope,

we may dare, with an unafraid boldness, to pray You, God, the holy Father, who art in the heavens, and say, “Our Father…”

Again, we see a movement from the Holy God who sanctifies and purifies the holy gifts, making His assembled people pure and holy as He is holy.

And finally, we come to the time of communion, the distribution of the holy mysteries. The Coptic rite consistently chants Psalm 150 throughout the entire year. I would just like to look at the first verse: ⲥⲙⲟⲩ ⲉⲫⲛⲟⲩϯ ϧⲉⲛ ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲧⲏⲣⲟⲩ ⲛⲧⲁϥ

Though the predominant liturgical translation at this point in the Coptic church is, “Praise God in all His saints” the majority of translations of the Scripture actually render, “Praise God in His sanctuary.” The Coptic does something quite beautiful though: it uses again ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ. Throughout the Scripture and in our liturgics, the word ⲛⲏⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ is used for holies, that is, persons, places, or things. There is an interchange that is allowed by this multipurpose meaning. “Praise God in all His holies”, His holy place—His heavenly throne, the gifts which He has descended upon, and each and every one of us who have become His dwelling by the partaking of His mysteries. It is not a haphazard choice to sing this hymn during communion. In partaking of His body and blood, we are the pinnacle of His divine economy, “For the glory of God is a living man; and the life of man consists in beholding God. For if the manifestation of God which is made by means of the creation, affords life to all living in the earth, much more does that revelation of the Father which comes through the Word, give life to those who see God.” – St Irenaeus