This past week, while studying the Coptic hymns of the Anaphora of St. Gregory Nazianzus with a newly ordained priest in our family, I stumbled upon a few significant issues in translation—from Greek to Coptic (Bohairic)/Greek to Arabic as well as the derivative English translation used currently by the Coptic Church). While there are a plethora of notes to discuss in this regard, I should think to focus on two essential points for this post: (1) a portion from the prayer after the Sanctus (second half of the thanksgiving) and (2) the first piece of the prayers of the Institution.

Although medieval manuscripts inform us that the Gregorian Anaphora ought to be prayed on Sundays throughout the year as well on feast days, Coptic faithful today seldomly experience this majestic and masterful service (oftentimes due to its length and musical complexity). It is, however, highly unlikely that one who attends this eucharistic prayer will ever forget it as long as he lives because of its theological depth, poetic nature, relatability, and expressive music.

As has been previously mentioned, the Gregorian Anaphora—like Basil and other Antiochene or West Syrian anaphorae—begins by worthily attributing praise, worship, and thanksgiving (etc.) to God on account of who He is by nature (i.e. the theology of God) and then calls the Church to participate with the heavenly hosts in ascribing holiness to the Lord in the chant of the Sanctus (cf. Isaiah 6). It is the following section which recounts what God has done for us men and for our salvation (i.e. the economy of God), that is our first stop in today’s discussion. It is perhaps the most memorable piece of the Gregorian Anaphora, etched into the minds and hearts of the Coptic people, beginning with, “Holy, holy are You, O Lord, and most-holy!”

Praying this masterpiece, the priest takes on the role of Adam, the first man, speaking on behalf of all humanity, and recounts the Lord’s economy. Although medieval manuscripts and modern books divide this composition into four segments by the laity’s interjection, “Lord, have mercy,” early evidence suggests that in its original construction, this composition was one contiguous whole uninterrupted. Interestingly, the points of separation differ between the Greek and Coptic recensions of the text, providing us with important insight as to how the text was initially understood and translated, clarifying a number of perplexities in current practice.

The general framework below may offer one plausible theory as to the reasoning behind the segmentation in the Coptic recension:

| ⲭⲟⲩⲁⲃ (Holy) | The Lord creates man; man instead chooses death. |

| ⲛⲑⲟⲕ ⲡⲁⲛⲏⲃ (You, My Master) | The Lord seeks after man, sends the prophets, provides help through the law. |

| ⲛⲑⲟⲕ [ⲡⲉ] ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ (You, He-Who-Is) | The Lord Himself enters the womb of the Virgin, becomes man, and reveals Himself to man. |

| ⲁⲕⲓ̈ ⲉⲡϧⲟⲗϧⲉⲗ (You came to the slaughter) | The Lord takes up the Cross, manifesting His great care for man, and shall return to judge. |

That being said, we now arrive at the heart of the first translation issue for today’s post. At the end of the second segment, the current Coptic text and English translation (Coptic Reader) reads:

| ϩⲱⲥ ⲟⲩⲱⲓⲛⲓ ⲙ̀ⲙⲏⲓ ⲁⲕϣⲁⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲥⲱⲣⲉⲙ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲉⲙⲓ | As true light, You have shone upon the lost and the ignorant. |

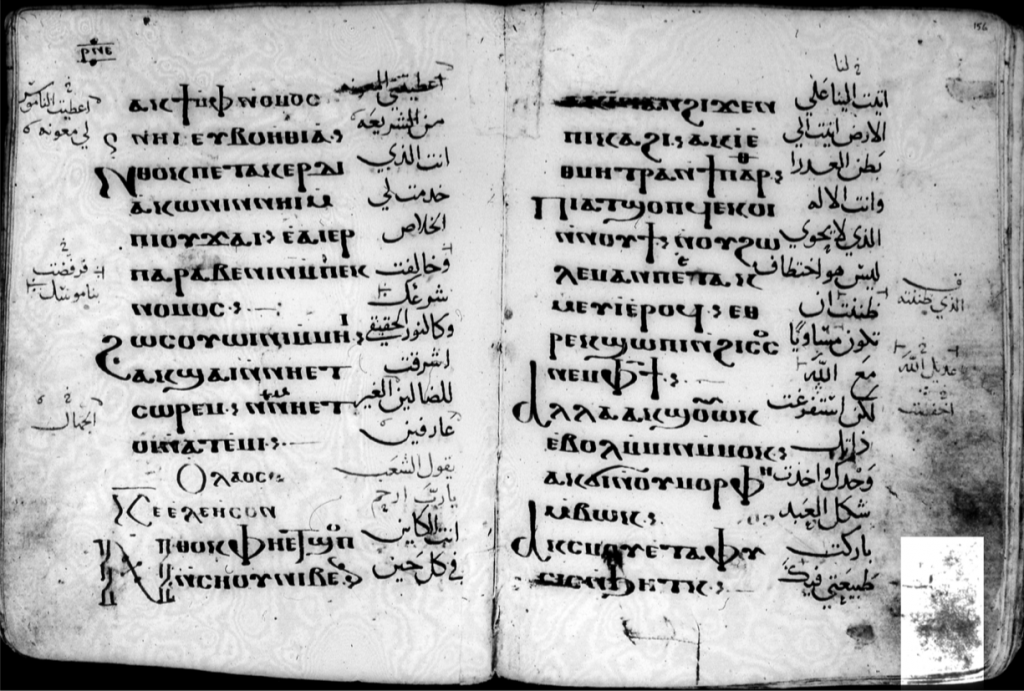

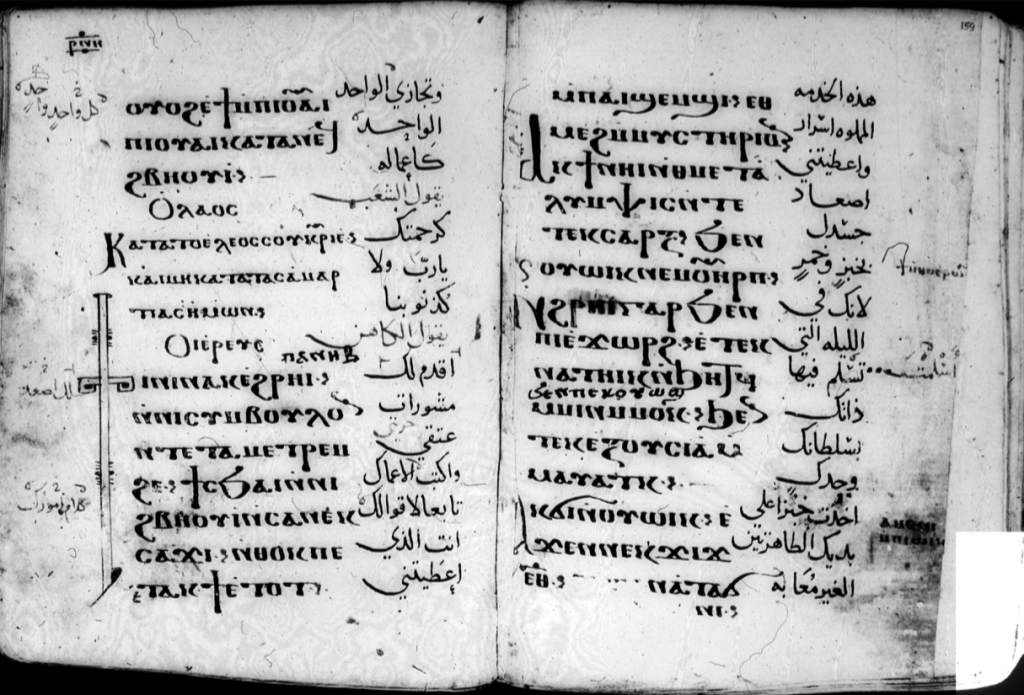

Had I not come across a slight variation in the earliest extant Bohairic recension in Bodl.Hunt.360, I may never have batted an eye at this line!

As you can see below, however, the pristine text (that is the original text written in the manuscript by the primary scribe) reads «ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲉⲙⲓ» instead of «ⲛⲉⲙ ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲉⲙⲓ», and the two letters «ⲉⲙ» were inserted by a later scribe, matching the text to what is currently seen in our books.

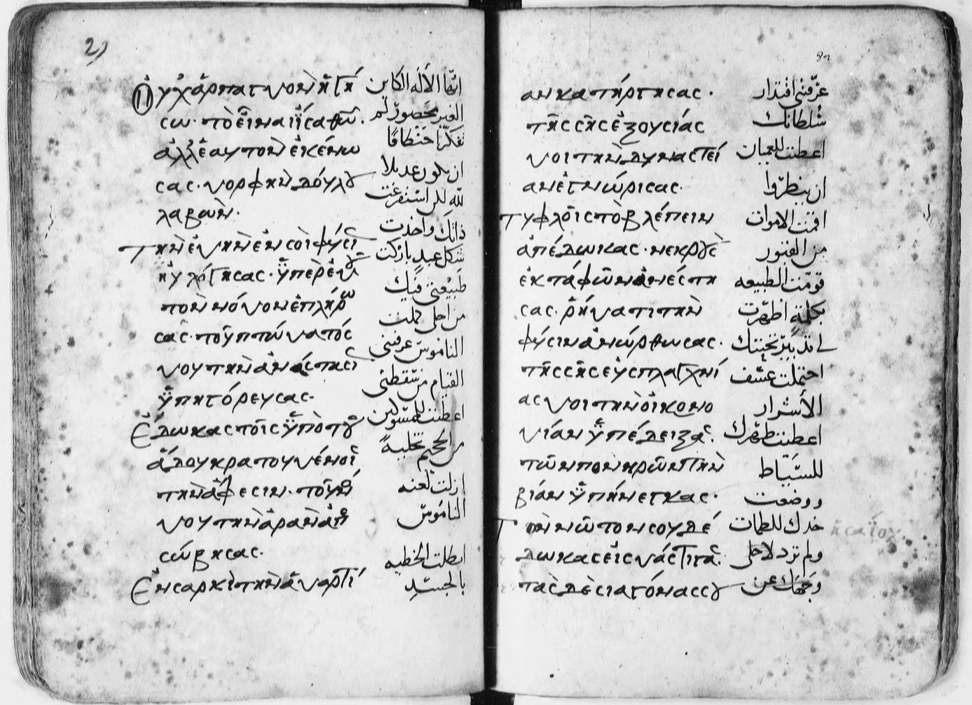

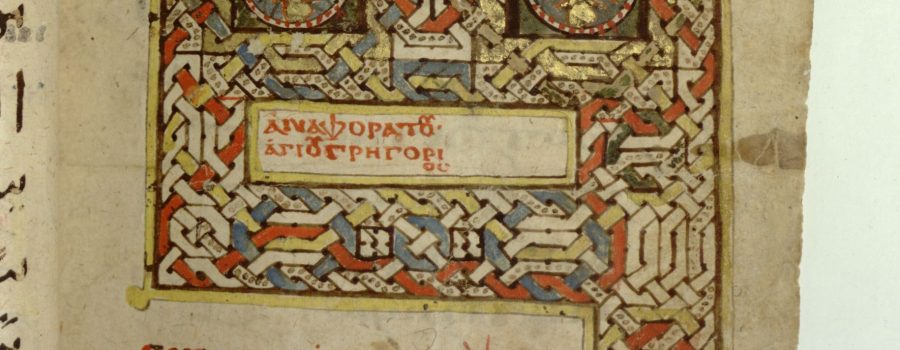

Bodl.Hunt.360 (~13th c.)

It is important to note that, although this manuscript was referenced in Ernst Hammerschmidt’s critical edition of the Bohairic Coptic text, this variant is omitted.

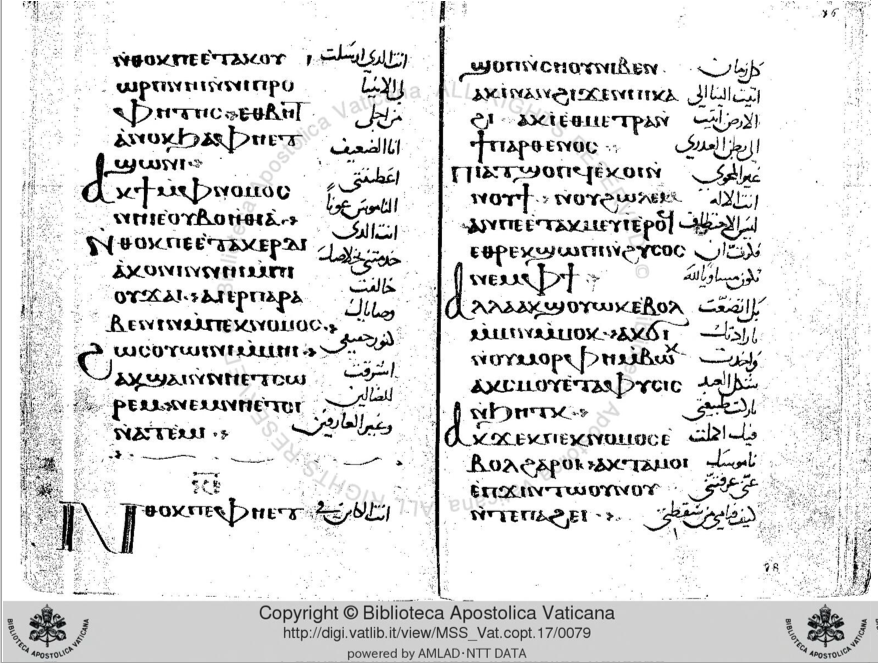

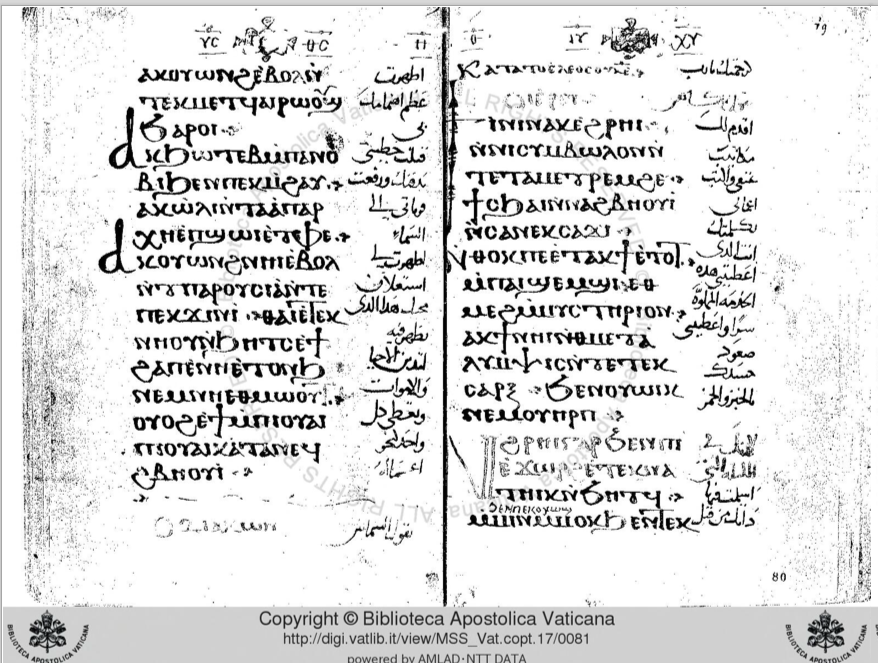

Vat.Copt.17 (AD 1288) depicts a stage in which the additional «ⲉⲙ» has been inserted into the principle text.

At first glance, this older reading is ambiguous at best. The intent of the scribes was most likely to correct what they assumed to be a mistake, but this obvious alteration led me to take a closer look at the Greek text of the Anaphora to perhaps find some clarity.

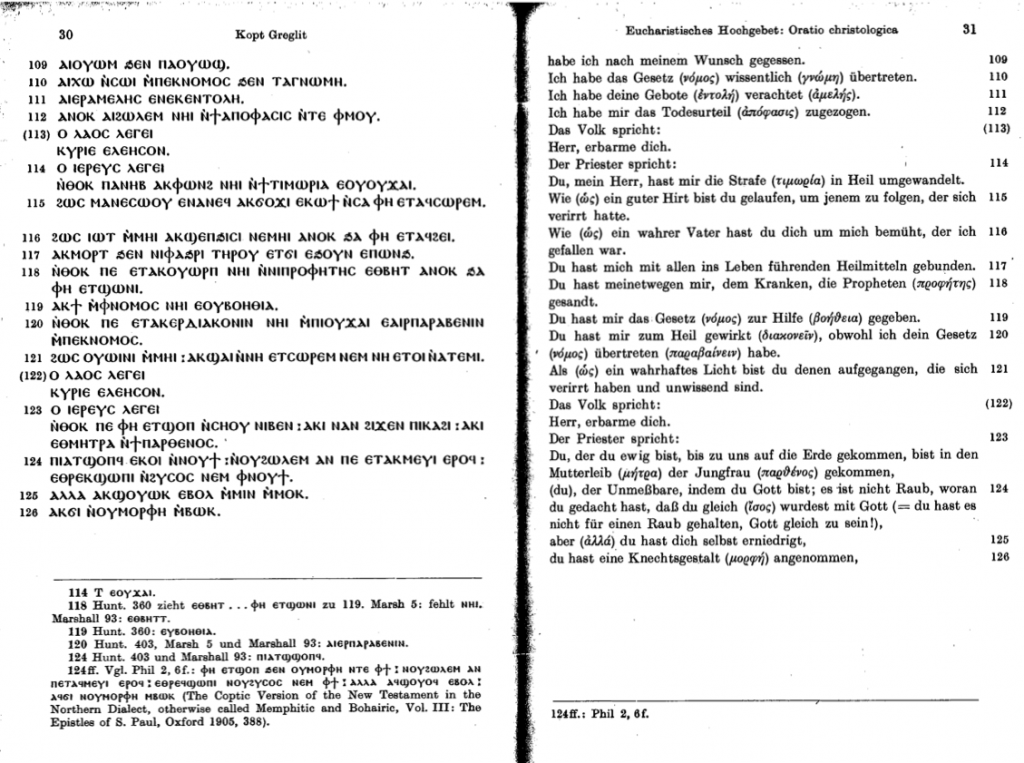

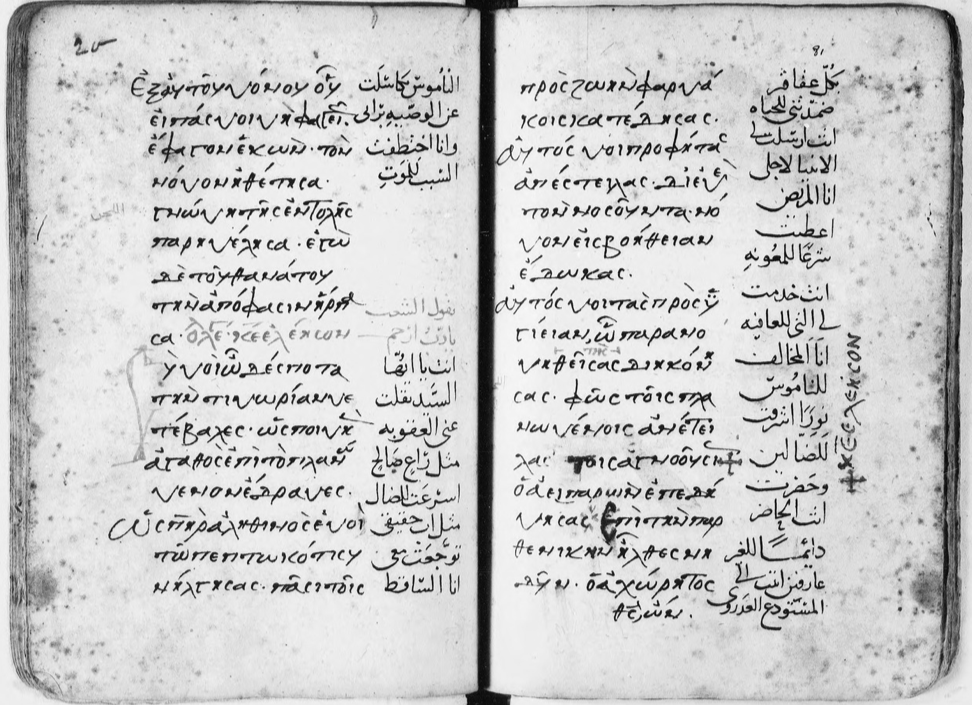

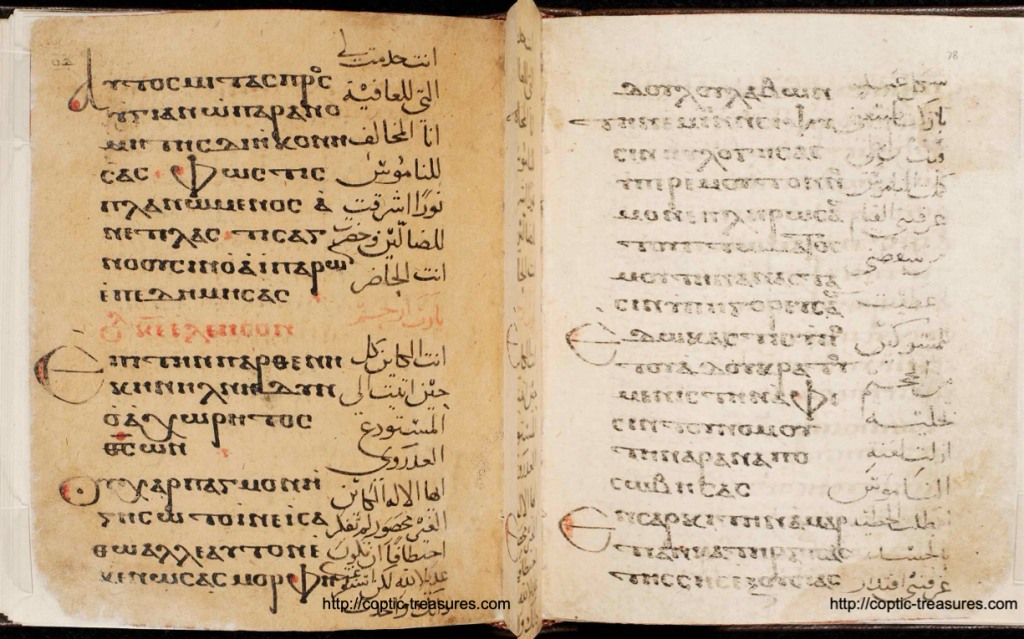

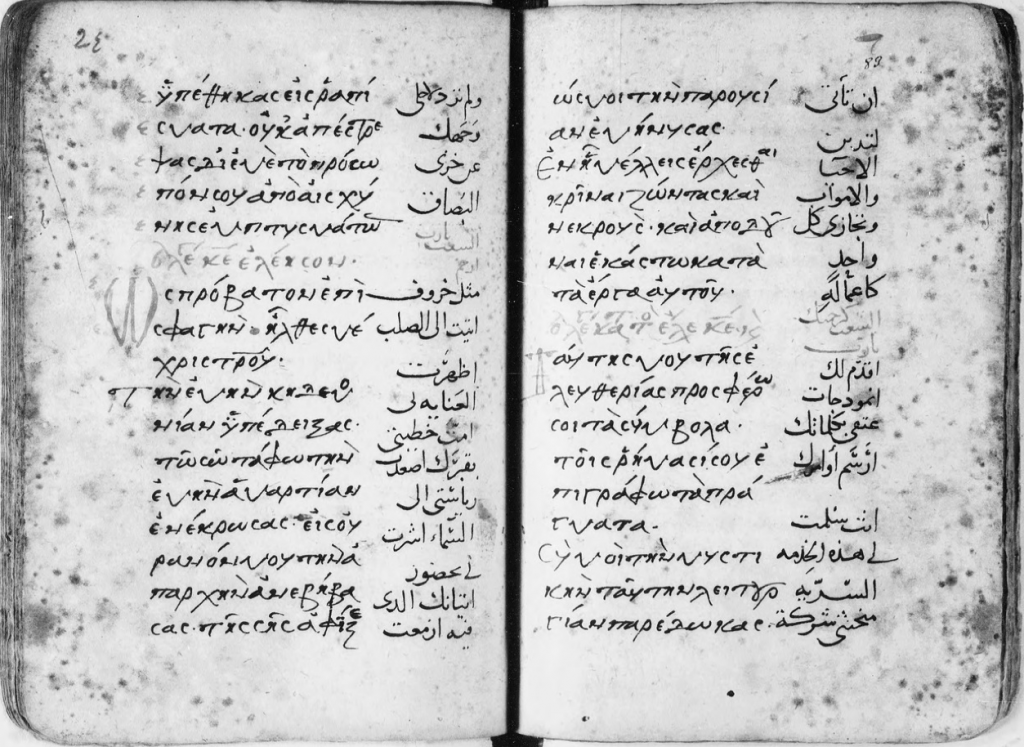

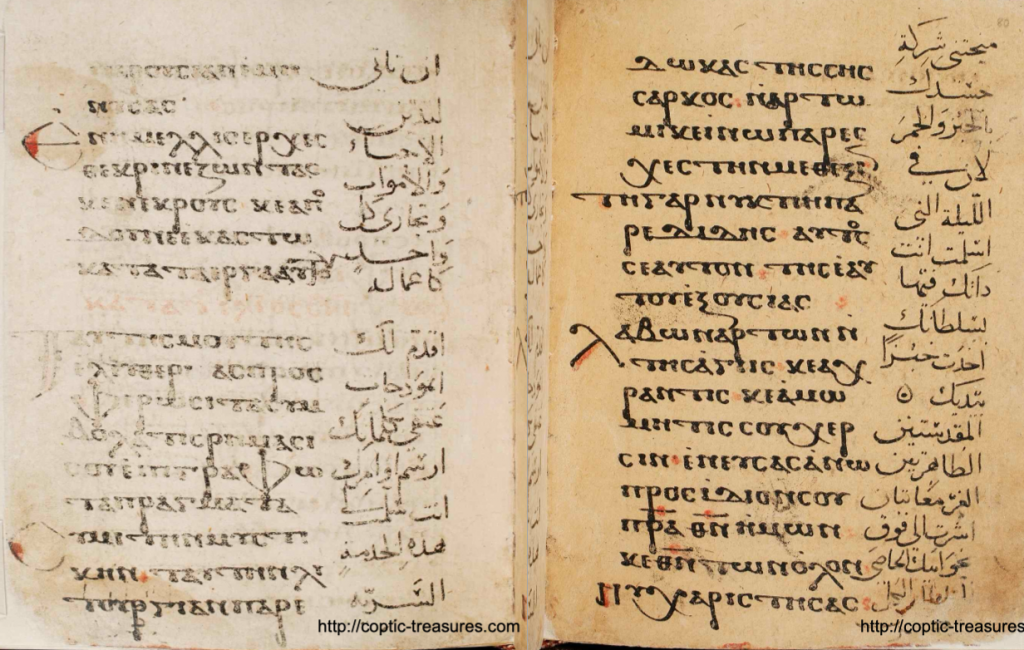

There are two manuscripts that contain the Anaphora of St. Gregory in Greek: (1) BnF.Graec.325 (likely of Melkite usage) and (2) Kacmarcik Codex (assumed to be of Coptic origin due to its phonetically transcribed text, design, etc.); both of these manuscripts date back to the 14th century. Below are the images of this section in these two manuscripts, respectively:

BnF.Graec.325

Despite the notion that this euchologion belonged to the Melkite tradition, it seems that it fell into Coptic hands at some point given that the inserted the ⲕⲩⲣⲓⲉ ⲉⲗⲉⲏⲥⲟⲛ in the margin of the folio on the right is certainly a Coptic script and it is placed exactly where the Coptic segmentation occurs.

Kacmarcik Codex

Publication of Kacmarcik Codex by the late Bishop Epiphanius of St. Macarius Monastery:

Comparative study of both aforementioned manuscripts by the same, Bishop Epiphanius:

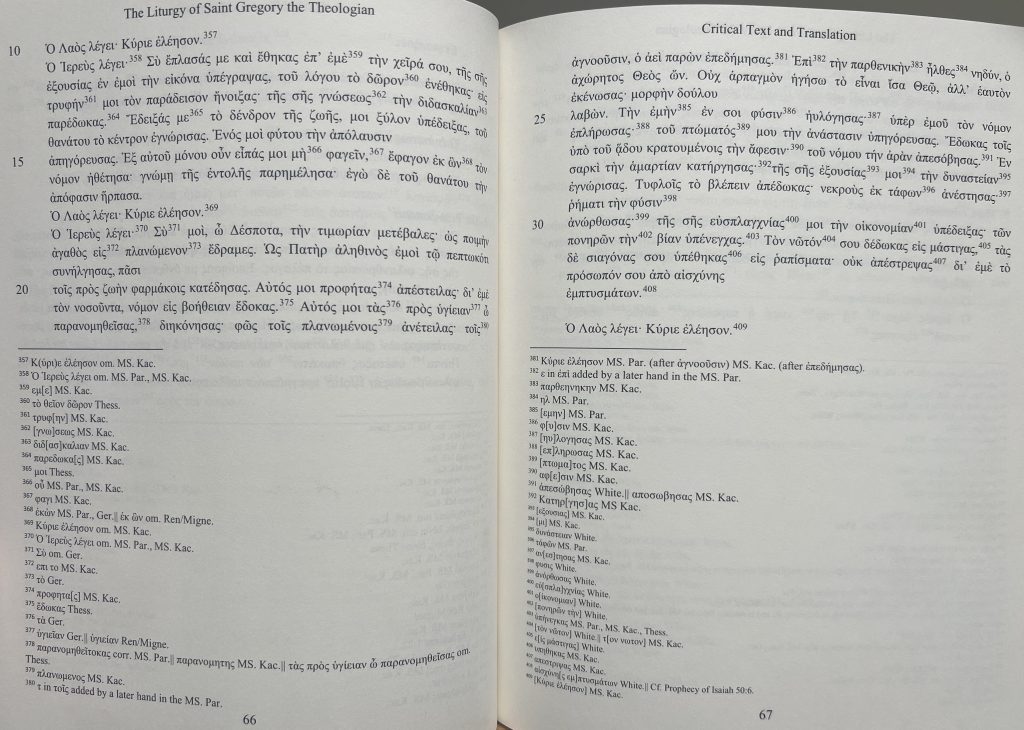

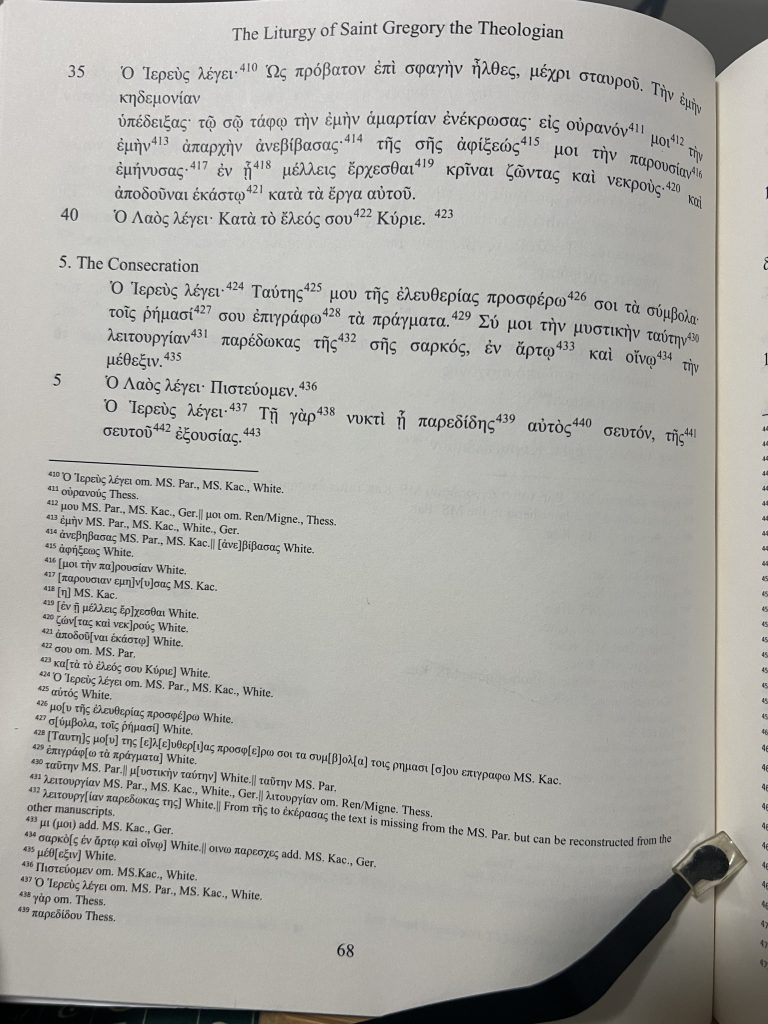

Most recently, Fr. Nicholas Newman published a pivotal critical edition of the Greek text with English translation and commentary (https://www.saintdominicsmedia.com/shop/the-liturgy-of-saint-gregory-the-theologian/):

From these manuscripts and publications, the Greek text has a slightly different reading than the current Coptic text and its English translation:

| φῶς τοῖς πλανωμένοις ἀνέτειλας | Light, for those who are wandering/lost, you have dawned; |

| τοῖς ἀγνοοῦσιν ὁ ἀεὶ παρὼν ἐπεδήμησας | for the ignorant, You, who are ever-present, have sojourned/resided in a foreign place. |

Here, there are two clauses, one for the lost and another for the ignorant! They are treated textually as separate entities, and for each of them Christ acts.

Now, we have learned from working on the Bohairic Psalmody that translators of Greek into Bohairic Coptic most often translate as literally as humanly possible—even at times where a literal translation could distort the intended meaning, or render syntax errors or grammatical complexities! As such, a comparison of the Greek text and Bohairic translation suggests the accuracy of the pristine recension in Bodl.Hunt.360:

| φῶς τοῖς πλανωμένοις ἀνέτειλας | Ϩⲱⲥ ⲟⲩⲱⲓⲛⲓ ⲙ̀ⲙⲏⲓ ⲁⲕϣⲁⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲥⲱⲣⲉⲙ ⳾ |

| τοῖς ἀγνοοῦσιν ὁ ἀεὶ παρὼν ἐπεδήμησας | ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲉⲙⲓ… |

The Greek τοῖς ἀγνοοῦσιν (in the dative case) meaning, “to/for the ignorant” is more precisely translated into Bohairic as ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲉⲙⲓ where the first ⲛ̀ serves as a preposition rendering the Greek dative! Hence, the Coptic would also be translated into English as: “As true light You have dawned to the lost/wandering; for the ignorant…” We do find ourselves in a predicament, however! Where is the rest of the statement? How is ὁ ἀεὶ παρὼν ἐπεδήμησας translated into Coptic?

The answer lies in the beginning of the next Coptic section ⲛⲑⲟⲕ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ!

Because we Copts are conditioned to read liturgical text as it is practiced in worship, we often fail to recognize the textual nuance. Let’s take a look at the same text without the interjected ⲕⲩⲣⲓⲉ ⲉⲗⲉⲏⲥⲟⲛ.

| φῶς τοῖς πλανωμένοις ἀνέτειλας | Ϩⲱⲥ ⲟⲩⲱⲓⲛⲓ ⲙ̀ⲙⲏⲓ ⲁⲕϣⲁⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲥⲱⲣⲉⲙ ⳾ |

| τοῖς ἀγνοοῦσιν ὁ ἀεὶ παρὼν ἐπεδήμησας | ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲉⲙⲓ ⲛⲑⲟⲕ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ⲛ̀ⲥⲏⲟⲩ ⲛⲓⲃⲉⲛ ⲁⲕⲓ̈ ⲛⲁⲛ ϩⲓϫⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲕⲁϩⲓ ⳾ |

“As true light, You have dawned upon the lost; for the ignorant, You who are ever-present/He-Who-Is at all times, have come to us on the earth.”

Arranged in this manner, the Bohairic translation is almost entirely in line with the Greek text with the exception of the additional clarification «ⲛⲁⲛ ϩⲓϫⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲕⲁϩⲓ» specifying Christ’s coming to earth and interpreting us to be the ignorant ones. Nevertheless, some confusion arises here from the Bohairic use of the Divine Name «ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ» to translate the Greek «ⲟ…παρὼν» likely leading to the insertion of the Coptic copula ⲡⲉ in later texts (i.e. ⲛⲑⲟⲕ ⲡⲉ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ) as is seen in common practice today.

Now then, if this phrase «ⲛⲑⲟⲕ ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ⲛ̀ⲥⲏⲟⲩ ⲛⲓⲃⲉⲛ ⲁⲕⲓ̈ ⲛⲁⲛ ϩⲓϫⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲕⲁϩⲓ belongs with the ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲉⲙⲓ» before it, what are we to make of the subsequent clauses?

The remainder of the phrase in the current Bohairic text and English translation (Coptic Reader) is as follows:

| ⲁⲕⲓ̈ ⲉⲑⲙⲏⲧⲣⲁ ⲛ̀ϯⲡⲁⲣⲑⲉⲛⲟⲥ | You have come into the womb of the Virgin. |

| ⲡⲓⲁⲧϣⲟⲡϥ ⲉⲕⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲛ̀ⲟⲩϩⲱⲗⲉⲙ ⲁⲛ ⲡⲉⲧⲁⲕⲙⲉⲩⲓ ⲉⲣⲟϥ ⲉⲑⲣⲉⲕϣⲱⲡⲓ ⲛ̀ϩⲩⲥⲟⲥ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲫϯ ⲁⲗⲗⲁ ⲁⲕϣⲟⲩⲱⲕ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲙ̀ⲙⲓⲛ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟϥ ⲁⲕϭⲓ ⲛ̀ⲟⲩⲙⲟⲣⲫⲏ ⲙ̀ⲃⲱⲕ | You, the Infinite, being God, did not consider equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied Yourself and took the form a servant. |

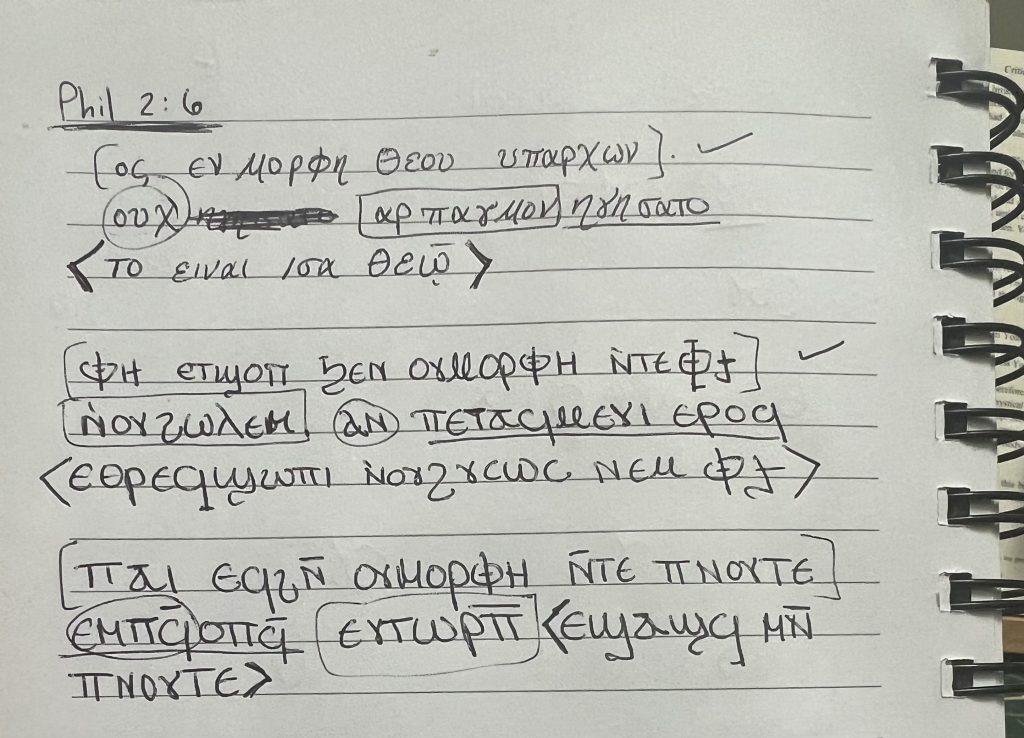

The latter portion of the text is taken directly from Philippians 2:6–7: “who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant…” This verse is another great example of the Bohairic translators being quite literal (even in word order) even at the expense of basic Coptic comprehension, whereas the Sahidic translators aimed more for the intent of the Greek. In order to decipher what was happening with the text in the anaphora, I attempted to parse the scriptural verse here (yes, I still do these things by hand!):

After clarifying how the verse in Philippians was to be understood, I was able to identify where the confusion arises in the Coptic translation of the anaphora: the phrase «ⲡⲓⲁⲧϣⲟⲡϥ ⲉⲕⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲟⲩϯ» was being interpreted as a substitute for «ⲫⲏⲉⲧϣⲟⲡ ϧⲉⲛ ⲟⲩⲙⲟⲣⲫⲏ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲫϯ» which equates to «ὁ ἀχώριτος θεὸς ὢν» being understood as a cognate of «ος εν μορφη θεου υπαρχων» (i.e. that “You, the Infinite, being God” was a replacement or rephrasing of “he being in the form of God).

At first glance, this might seem to be a reasonable conclusion; however, the term «ἀχώριτος» / «ⲡⲓⲁⲧϣⲟⲡϥ» struck me as less related to the quotation from scripture and more directly linked with the previous phrase about the virginal womb. Here’s why:

1) In the overarching Orthodox tradition (and more specifically in the Coptic mind) there is an emphasis on the idea of the Uncontainable/Limitless/Boundless One being contained in the virginal womb. We can see this clearly in one of the ⲁⲇⲁⲙ doxologies for the Virgin Mary:

| Ⲛⲑⲟ ⲑⲙⲁⲩ ⲙ̀ⲡⲓⲟⲩⲱⲓⲛⲓ ⳾ ⲉⲧⲧⲁⲓⲏⲟⲩⲧ ⲙ̀ⲙⲁⲥⲛⲟⲩϯ ⳾ ⲁⲣⲉϥⲁⲓ ϧⲁ ⲡⲓⲗⲟⲅⲟⲥ ⳾ ⲡⲓⲁⲭⲱⲣⲓⲧⲟⲥ ⳾ | You, O Mother of Light, • honored Mother of God, • have carried the Word, • the Uncontainable One; • |

2) The Greek text in both BnF.Graec.325 and the Kacmarcik Codex place «ὁ ἀχώριτος θεὸς ὢν» in juxtaposition with «ἐπι τὴν παρθενικὴν ῇλθες νηδύν» and begin the next indented paragraph with «οὐχ ἁρπαγμὸν ἡγήσω» (as you can see in the images shown above).

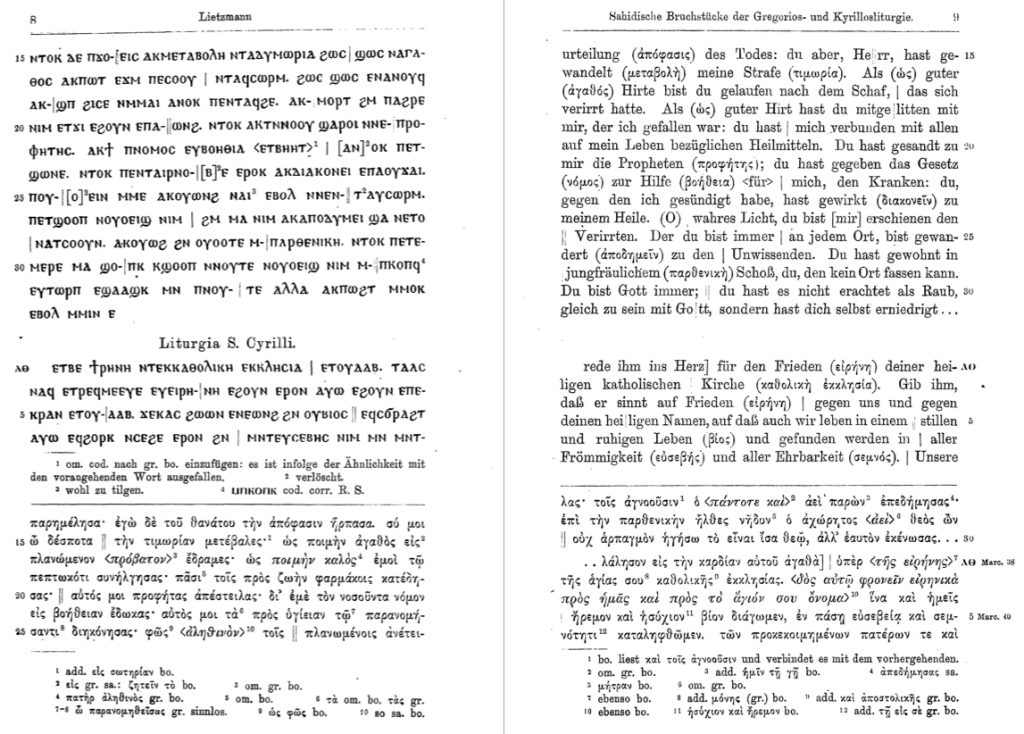

3) The Sahidic text of the Gregorian Anaphora

In Lietzmann’s critical edition of the Sahidic Text as well as Bishop Epiphanius’ edition of the White Monastery Euchologion (shown below, respectively), the Sahidic text contains an additional gloss:

| ⲟⲉⲓ︦ⲛ ⲙ︦ⲙⲉ︦ ⲁⲕⲟ︦ⲩⲱⲛϩ ⲛⲁⲓ̈ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲛⲛⲉⲛⲧⲁⲩⲥⲱⲣⲙ | You have shown me the true light for the lost; |

| ⲡⲉⲧϣⲟⲟⲡ ⲛⲟⲩⲟⲉⲓ̈ϣ ⲛⲓ̈ⲙ ϩⲙ ⲙⲁ ⲛⲓ̈ⲙ ⲁⲕⲁⲡⲟⲇⲩⲙⲉⲓ︦ ϣⲁ ⲛⲉⲧⲟⲛⲁⲧⲥⲟⲟⲩⲛ︦ | He-Who-Is / You who are present at all times and in every place, You sojourned to the ignorant. |

| ⲁⲕⲟⲩⲱϩ ϩⲛ ⲟⲩⲟⲟⲧⲉ ⲙ︦ⲡⲁⲣⲑⲉⲛⲓ̈ⲕⲏ ⲛⲧⲟⲕ ⲡⲉⲧⲉ ⲙⲉⲣⲉ ⲙⲁ ϣⲟ︦ⲡⲕ ⲕϣⲟⲟⲡ ⲛⲛⲟⲩⲧⲉ ⲛⲟⲩⲟⲉⲓ︦ϣ ⲛⲓ̈ⲙ | You dwelt in the virginal womb, You whom no place can contain being God—at all times— |

| ⲙ︦ⲡⲕⲟⲡⲕ ⲉⲩⲧⲱⲣⲡ ⲉϣⲁⲁϣⲕ ⲙⲛ ⲡⲛⲟⲩⲧⲉ ⲁⲗⲗⲁ ⲁⲕⲡⲱϩⲧ ⲙⲙⲟⲕ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲙⲙⲓ̈ⲛ ⲉ | You did not consider equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied Yourself… |

The Sahidic use of ⲟⲩⲱϩ “to dwell” to translate the Greek derivative of ἔρχομαι “to go” as well as the very specific «ⲛⲧⲟⲕ ⲡⲉⲧⲉ ⲙⲉⲣⲉ ⲙⲁ ϣⲟ︦ⲡⲕ ⲕϣⲟⲟⲡ ⲛⲛⲟⲩⲧⲉ» to render «ὁ ἀχώριτος θεὸς ὢν» emphasizes the focus on the paradoxical containment of God—the One who cannot be contained or bound in any place dwelt in the womb of the Virgin!

Comparing the Bohairic, Sahidic, and Greek texts, we are then able to more precisely assess the intent of the Coptic translations (e.g. ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲟⲓ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲉⲙⲓ in Bohairic is rendered as ϣⲁ ⲛⲉⲧⲟⲛⲁⲧⲥⲟⲟⲩⲛ︦ in Sahidic making clear that the ⲛ̀ construction in the Bohairic is the intended meaning), and identify the origin, or at least, the pathway of certain features (e.g. ⲙ̀ⲙⲏⲓ in Bohairic, not found in Greek, but present as ⲙ︦ⲙⲉ︦ in Sahidic).

Thus, altogether, this section of the Gregorian Anaphora would be more correctly rendered as:

“As true Light, you have dawned upon the lost; to the ignorant, You, He-Who-Is at all times, have come to us on the earth. You, while being Uncontainable God, came to the womb of the Virgin. You did not consider equality with God a thing to be grasped/seized, but emptied Yourself and took the form of a servant…”

Before transitioning to the next major translation issue, I must not overlook an essential underlying concept throughout this entire piece: the distinction between grasping/seizing/snatching and emptying/giving.

In a poetic attempt, the modern English translations used in the Coptic Church render the phrase, “I plucked for myself the sentence of death,” referring to the fruit eaten from the tree. This choice of words makes it extremely difficult to draw the connection later in the anaphora when St Paul’s letter to the Philippians is referred to regarding equality with God as a thing not to be grasped. This is increasingly more difficult to do when praying in a Church service today where the screens only show you one or two lines at a time!

Thankfully, however, the Coptic and Greek texts of the Gregorian Anaphora, use the same terms (ϩⲱⲗⲉⲙ and ἁρπάζω) in both instances, easily drawing the necessary connection between Adam and Eve’s attempt to seize divinity (Gen 3:5) and Christ’s self-emptying (kenosis) as treated in Pauline literature (Phil 2:7). Whereas Adam, and all humanity in him, sought to snatch being god, by his own will disobeying the command of God, Christ empties Himself to give man what is His, in obedience to the will of His Father. And as Adam disobeyed the commandment of the Lord to not eat from the tree, the priest now, and all of us with him, obeys the new command: “Take eat…Take Drink…This do…,” partaking from the tree of life, namely the body and the blood of God.

Hence, we will now discuss the introduction of the Institution in the Anaphora of Gregory. As we always do, let’s take a look at the current Coptic text and English translation (CR), compare it with the text in our manuscript tradition and learn from credible scholarly work!

| Ϯⲓⲛⲓ ⲛⲁⲕ ⲉϩⲣⲏⲓ ⲡⲁⲛⲏⲃ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓⲥⲩⲙⲃⲟⲩⲗⲟⲛ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲧⲁⲙⲉⲧⲣⲉⲙϩⲉ | I offer You, O my Master, the symbols of my freedom. |

| ϯⲥϧⲁⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲁϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ ⲛ̀ⲥⲁ ⲛⲉⲕⲥⲁϫⲓ | I write my works according to Your sayings. |

| ⲛⲑⲟⲕ ⲡⲉ ⲉⲧⲁⲕϯ ⲉⲧⲟⲧ ⲙ̀ⲡⲁⲓϣⲉⲙϣⲓ ⲉⲑⲙⲉϩ ⲙ̀ⲙⲩⲥⲧⲏⲣⲓⲟⲛ | You are he who has given me this service full of mystery. |

| ⲁⲕϯ ⲛⲏⲓ ⲛ̀ⲑⲙⲉⲧⲁⲗⲩⲙⲯⲓⲥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲧⲉⲕⲥⲁⲣⲝ ϧⲉⲛ ⲟⲩⲱⲓⲕ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲟⲩⲏⲣⲡ | You have given me the partaking of Your flesh in bread and wine. |

Due to the ambiguity of the English translation (and the Arabic translation from which it is derived) our people often interpret this opening of the consecratory prayers as a compilation of independent statements; the “symbols” are left undefined, the “works” being written are unknown, and despite the remainder of the entire anaphora being written in the first person, many understand this prayer to be specifically pertaining to the priest alone.

Analyzing the text in Bodl.Hunt.360, once more we find a number of variants: (1) ⲡⲁⲛⲏⲃ (my Master) is omitted in the pristine text, but appended later by the same hand that added «ⲉⲙ»; (2) ⲛⲁϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ is written as ⲛⲓϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ (which we will discuss in more detail shortly); and (3) the following piece ⲛϩⲣⲏⲓ ⲅⲁⲣ is directly attached to ϯⲓⲛⲓ ⲛⲁⲕ without being interrupted by ⲡⲓⲥⲧⲉⲩⲟⲙⲉⲛ which again indicates that these interjections should not hinder us from reading the text as a contiguous whole.

Again, Vat.Copt.17 (AD 1288) witnesses to a stage in which the text has begun to shift ever so slightly; in this case, only ⲛⲓϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ has been altered into ⲛⲁϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ.

Of note, Hammerschmidt’s critical text of the Bohairic omits these seemingly minor variants. When seen in light of the Greek text, however, these variants become of the utmost significance.

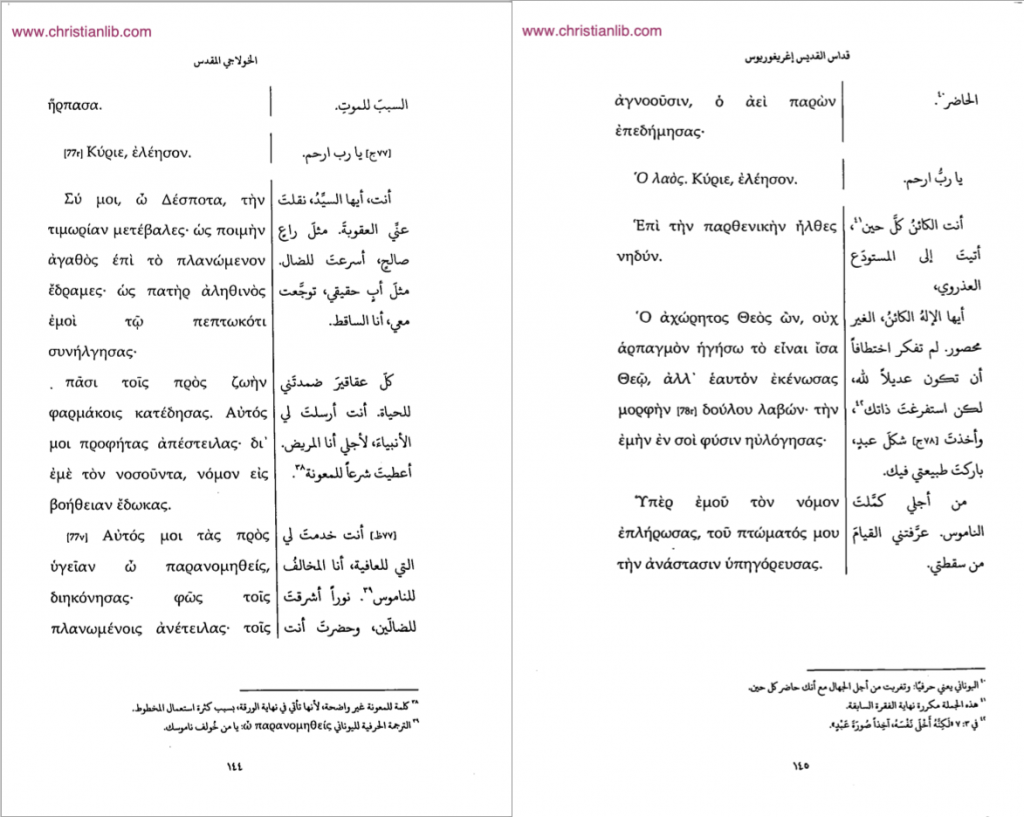

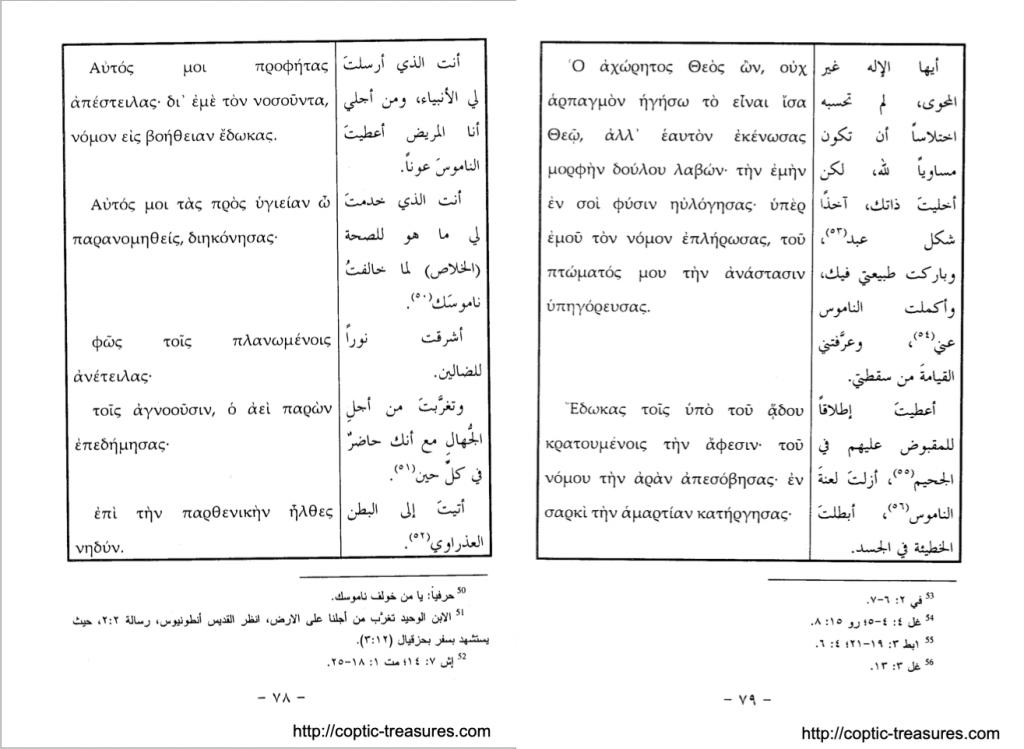

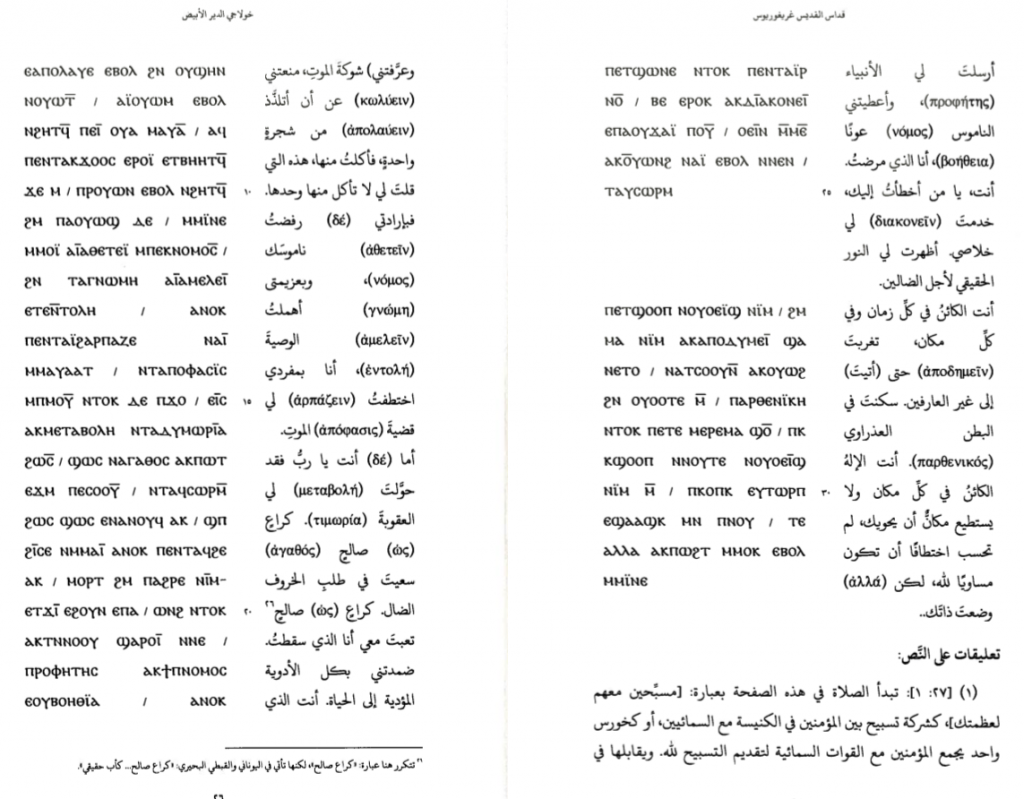

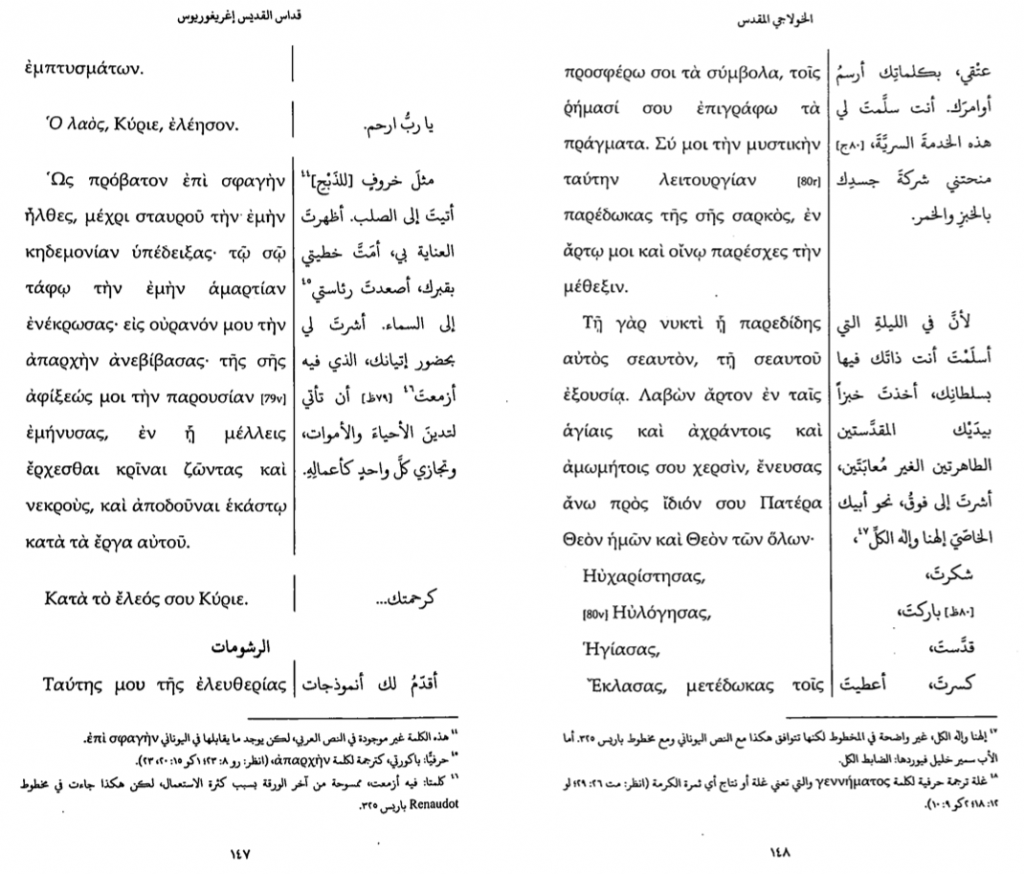

Let us rely once more on BnF.Graec.325, Kacmarcik Codex, Bishop Epiphanius’ and Fr. Nicholas Newman’s editions of the Greek:

BnF.Graec.325

Kacmarcik Codex

Bishop Epiphanius Publication of the Kacmarcik Codex

Fr Nicholas Newman’s Critical Edition

In June of 2025, Dr. Sameh Farouk, Professor of Byzantine Literature at Cairo University, presented a lecture on this very topic and arrived at a few helpful conclusions:

(1) A clear contrast is being made in the Greek between τὰ σὐμβολα vs. τὰ πράγματα (the symbols vs. the realities)—the symbols being the bread and the wine, and the realities being the body and blood of our Savior.

(2) In this instance, the use of the word επιγράφω likely takes on the definition, “I ascribe,” rather than “I write,” or “I inscribe.”

(3) The words being referred to are the sayings of Christ in the consecratory prayers.

Thus, we arrive at the following:

| Ταύτης μου τῆς ἐλευθερίας προσφέρω σοι τὰ σὐμβολα• | Ϯⲓⲛⲓ ⲛⲁⲕ ⲉϩⲣⲏⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓⲥⲩⲙⲃⲟⲩⲗⲟⲛ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲧⲁⲙⲉⲧⲣⲉⲙϩⲉ | I offer to You the symbols of my freedom; |

| τοῖς ῥήμασί σου επιγράφω τὰ πράγματα. | ϯⲥϧⲁⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ ⲛ̀ⲥⲁ ⲛⲉⲕⲥⲁϫⲓ | to your words, I ascribe the realities. |

| Σύ μοι τὴν μυστικὴν ταύτην λειτουργίαν | ⲛⲑⲟⲕ ⲡⲉ ⲉⲧⲁⲕϯⲉⲧⲟⲧ ⲙ̀ⲡⲁⲓϣⲉⲙϣⲓ ⲉⲑⲙⲉϩ ⲙ̀ⲙⲩⲥⲧⲏⲣⲓⲟⲛ | You have given to me this mystical liturgy/service: |

| παρέδωκας τῆς σῆς σαρκός, ἐν ἄρτῳ καὶ ὄινῳ τὴν μέθεξιν. | ⲁⲕϯ ⲛⲏⲓ ⲛ̀ⲑⲙⲉⲧⲁⲗⲩⲙⲯⲓⲥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲧⲉⲕⲥⲁⲣⲝ ϧⲉⲛ ⲟⲩⲱⲓⲕ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲟⲩⲏⲣⲡ | You have given me the partaking of Your flesh—in bread and wine. |

There are a number of points that I would like to add to Dr. Sameh’s findings as well:

(1) Coptic verb ⲓⲛⲓ + adv. ⲉϩⲣⲏⲓ (often ⲉⲡϣⲱⲓ in Bohairic) can carry the connotation of offering up which is likely the intent here in the anaphora. Like the Greek text, early Coptic manuscripts omit ⲡⲁⲛⲏⲃ (as we have previously mentioned).

(2) The construction ⲉⲑⲙⲉϩ ⲛ̀/ⲙ̀ is often a literal Coptic method of translating adjectival suffices such as “-ious,” e.g. ⲉⲑⲙⲉϩ ⲛ̀ⲱⲟⲩ = glorious, or “-ical” e.g. ⲉⲑⲙⲉϩ ⲙ̀ⲙⲩⲥⲧⲏⲣⲓⲟⲛ = mystical. This also aligns with the use of μυστικὴν in this text.

(3) Two manuscripts in Hammerschmidt’s critical text render the variant «ⲉⲁⲕϯ ⲛⲏⲓ ⲛ̀ⲑⲙⲉⲧⲁⲗⲩⲙⲯⲓⲥ» which would cause the translation to read: You gave me this mystical service, having given me the partaking of Your flesh in bread and wine.”

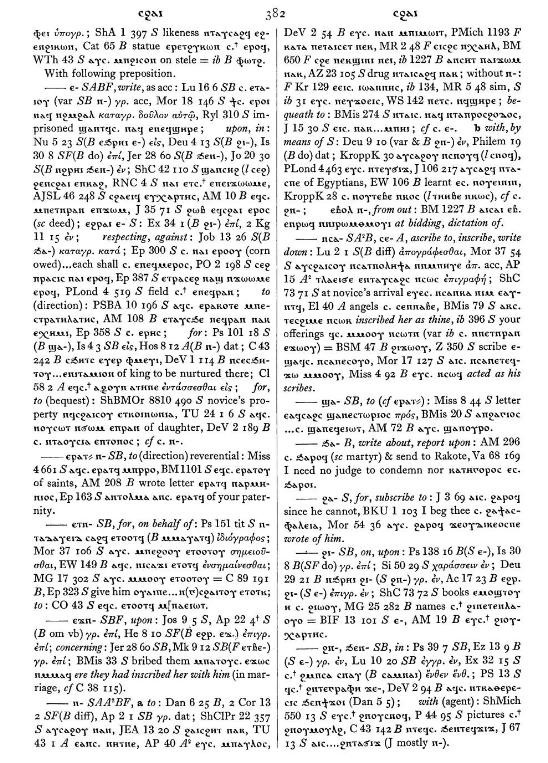

(4) When Coptic ⲥϧⲁⲓ is followed by the preposition ⲛ̀ⲥⲁ, the primary definition given is “ascribe to,” meaning that those who translated the Coptic from Greek likely had this understanding of επιγράφω, too. The Coptic Dictionary by Crum documents this clearly:

(5) The Coptic word «ϩⲱⲃ» (pl. ϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ) which is used as an equivalent of three different Greek words ([εργον, πραγμα, ποιημα] being just a few) has a range of meanings including: “thing, work, matter, event.” Earlier in the Anaphora of St. Gregory, the word «ϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ» is used to translate Greek «εργον» when referring to the deeds/works for which man will be judged; yet, just a few lines later, we see the same word «ϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ» employed to translate the Greek «πραγμα» meaning “thing” or “concrete reality.” It is likely this range of meaning ascribed (pun intended) to «ϩⲱⲃ» has allowed for the shift in understanding wherein “the realities” (i.e. the hidden reality of the Lord’s body and blood manifested in the symbols of bread and wine) to “the works” later becoming “my works,” referring to the actions of the priest (possibly the rubrics of the consecratory prayers).

(6) Furthermore, as Dr. Sameh indicated, the ambiguous “Your words” likely refers to the words uttered by Christ in the institution of the eucharistic mystery. The reality that these symbols of bread and wine manifest the body and blood of the Lord is made certain by the words of Christ Himself in His commandment to us enact His remembrance: “Take eat, this is My body…This, do…” and “Take drink, this is my blood…This, do…”

It is of great importance that we read here the consecratory prayer as a whole:

| Ϯⲓⲛⲓ ⲛⲁⲕ ⲉϩⲣⲏⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓⲥⲩⲙⲃⲟⲗⲟⲛ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲧⲁⲙⲉⲧⲣⲉⲙϩⲉ ⳾ ϯⲥϧⲁⲓ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓϩⲃⲏⲟⲩⲓ ⲛ̀ⲥⲁ ⲛⲉⲕⲥⲁϫⲓ ⳾ ⲛ̀ⲑⲟⲕ ⲡⲉ ⲉⲧⲁⲕϯ ⲉⲧⲟⲧ ⲙ̀ⲡⲁⲓϣⲉⲙϣⲓ ⲉⲑⲙⲉϩ ⲙ̀ⲙⲩⲥⲧⲏⲣⲓⲟⲛ ⳾ ⲁⲕϯ ⲛⲏⲓ ⲛ̀ⲑⲙⲉⲧⲁⲗⲩⲙⲯⲓⲥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲧⲉⲕⲥⲁⲣⲝ ϧⲉⲛ ⲟⲩⲱⲓⲕ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲟⲩⲏⲣⲡ ⳾ ⲛϩⲣⲏⲓ ⲅⲁⲣ ϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲉϫⲱⲣϩ ⲉⲧⲉⲕⲛⲁⲧⲏⲓⲕ ⲛ̀ϧⲏⲧϥ ϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲉⲕⲟⲩⲱϣ ⲙ̀ⲙⲓⲛ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲕ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲧⲉⲝⲉⲟⲩⲥⲓⲁ ⲙ̀ⲙⲁⲩⲁⲧϥ ⳾ ⲁⲕϭⲓ ⲛ̀ⲟⲩⲱⲓⲕ ⲉϫⲉⲛ ⲛⲉⲕϫⲓϫ ⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲁϭⲛⲓ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲁⲧⲑⲱⲗⲉⲃ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲙ̀ⲙⲁⲕⲁⲣⲓⲟⲛ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲣⲉϥⲧⲁⲛϧⲟ ⳾ ⲁⲕⲥⲟⲙⲥ ⲉⲡϣⲱⲓ ⲉⲧⲫⲉ ϩⲁ ⲫⲏⲉⲧⲉ ⲫⲱⲕ ⲛ̀ⲓⲱⲧ ⲫϯ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲫⲛⲏⲃ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲟⲩⲟⲛ ⲛⲓⲃⲉⲛ ⳾ ⲉⲧⲁⲕϣⲉⲡϩⲙⲟⲧ ⲁⲕⲥⲙⲟⲩ ⲉⲣⲟϥ ⲁⲕⲉⲣⲁⲅⲓⲁⲍⲓⲛ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟϥ ⲁⲕⲫⲁϣϥ ⲁⲕⲧⲏⲓϥ ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲉ ⲛⲟⲩⲕ ⲉⲧⲧⲁⲓⲏⲟⲩⲧ ⲛ̀ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲙ̀ⲙⲁⲑⲏⲧⲏⲥ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲟⲥ ⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲉⲕϫⲱ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲥ ⳾ ϫⲉ ϭⲓ ⲟⲩⲱⲙ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲛ̀ϧⲏⲧϥ ⲧⲏⲣⲟⲩ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲅⲁⲣ ⲡⲉ ⲡⲁⲥⲱⲙⲁ ⲉⲧⲟⲩⲛⲁⲫⲁϣϥ ⲉϫⲉⲛ ⲑⲏⲛⲟⲩ ⲛⲉⲙ ϩⲁⲛⲕⲉⲙⲏϣ ⳾ ⲛ̀ⲥⲉⲧⲏⲓϥ ⲉⲡⲭⲱ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲛⲓⲛⲟⲃⲓ ⳾ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲁⲣⲓⲧϥ ⲉⲡⲁⲉⲣⲫⲙⲉⲩⲓ ⳾ ⲡⲁⲓⲣⲏϯ ⲟⲛ ⲙⲉⲛⲉⲛⲥⲁ ⲑⲣⲟⲩⲟⲩⲱⲙ ⲁⲕϭⲓ ⲛ̀ⲟⲩⲁⲫⲟⲧ ⲁⲕⲑⲟⲧϥ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲟⲩⲧⲁϩ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ϯⲃⲱ ⲛ̀ⲁⲗⲟⲗⲓ ⲛⲉⲙ ⲟⲩⲙⲱⲟⲩ ⳾ ⲉⲧⲁⲕϣⲉⲡϩⲙⲟⲧ ⲁⲕⲥⲙⲟⲩ ⲉⲣⲟϥ ⲁⲕⲉⲣⲁⲅⲓⲁⲍⲓⲛ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟϥ ⲁⲕϫⲉⲙϯⲡⲓ ⲁⲕⲧⲏⲓϥ ⲟⲛ ⲛ̀ⲛⲏⲉⲧⲉ ⲛⲟⲩⲕ ⲉⲧⲧⲁⲓⲏⲟⲩⲧ ⲛ̀ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲙ̀ⲙⲁⲑⲏⲧⲏⲥ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲟⲥ ⲉⲑⲟⲩⲁⲃ ⲉⲕϫⲱ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲥ ⳾ ϫⲉ ϭⲓ ⲥⲱ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲛ̀ϧⲏⲧϥ ⲧⲏⲣⲟⲩ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲅⲁⲣ ⲡⲉ ⲡⲁⲥⲛⲟϥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ϯⲇⲓⲁⲑⲏⲕⲏ ⲙ̀ⲃⲉⲣⲓ ⲉⲧⲟⲩⲛⲁⲫⲟⲛϥ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲉϫⲉⲛ ⲑⲏⲛⲟⲩ ⲛⲉⲙ ϩⲁⲛⲕⲉⲙⲏϣ ⳾ ⲛ̀ⲥⲉⲧⲏⲓϥ ⲉⲡⲭⲱ ⲉⲃⲟⲗ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲛⲓⲛⲟⲃⲓ ⳾ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲁⲣⲓⲧϥ ⲉⲡⲁⲉⲣⲫⲙⲉⲩⲓ ⳾ Ⲥⲟⲡ ⲅⲁⲣ ⲛⲓⲃⲉⲛ ⲉⲧⲉⲧⲉⲛⲛⲁⲟⲩⲱⲙ ⲉⲃⲟⲗϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲁⲓⲱⲕ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲟⲩⲟϩ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉⲧⲉⲛⲥⲱ ⲉⲃⲟⲗϧⲉⲛ ⲡⲁⲓⲁⲫⲟⲧ ⲫⲁⲓ ⲉⲣⲉⲧⲉⲛϩⲓⲱⲓϣ ⲙ̀ⲡⲁⲙⲟⲩ ⲉⲣⲉⲧⲉⲛⲉⲣⲟⲙⲟⲗⲟⲅⲓⲛ ⲛ̀ⲧⲁⲁⲛⲁⲥⲧⲁⲥⲓⲥ ⲉⲣⲉⲧⲉⲛⲓⲣⲓ ⲙ̀ⲡⲁⲙⲉⲩⲓ ϣⲁ ϯⲓ̈ ⳾ | “I offer You the symbols of my freedom; I ascribe the realities to Your words! It is You who has given me this mystical service. You have given me the partaking of Your flesh in bread and wine—for in the night in which You gave Yourself [up] of Your own will and Your authority alone, You took bread into Your holy, spotless, unblemished, life-giving hands, and looked up towards heaven to Him who is Your Father, God, and Master of everyone, and when You gave thanks, You blessed it, sanctified it, broke it, and gave it to Your saintly honored disciples and holy apostles, saying, ‘Take, eat of it, all of you, for this is My body which will be/is broken for you and for many, given for the remission of sins—this, do as/for My remembrance.’ And, likewise, after they had eaten, You took a cup and mixed it with the fruit of the vine and water, and when You gave thanks, You blessed it, sanctified it, tasted it, and gave it to Your saintly disciples and holy apostles saying, ‘Take, drink of it, all of you, for this is My blood of the new covenant, which will be/is shed for you and for many, given for the remissions of sins—this, do as/for My remembrance.’ For every time you eat of this bread and drink of this cup, you proclaim My death, confess My resurrection, and remember Me until I come.” |

In one of the many fervent liturgical discussions that my friend, Mina Hani Samy, and I have had after watching Dr. Sameh’s lecture (one that is still ongoing might I add) we also came across another layer of context that could prove beneficial for interpreting this beautiful prayer—viewing through another lens, if you will.

The key terms in the Greek text of this prayer: σὐμβολα | ἐλευθερίας | πράγματα | ῥήμασί | are all employed as terms within legal documentation surrounding the manumission of slaves in Byzantium.

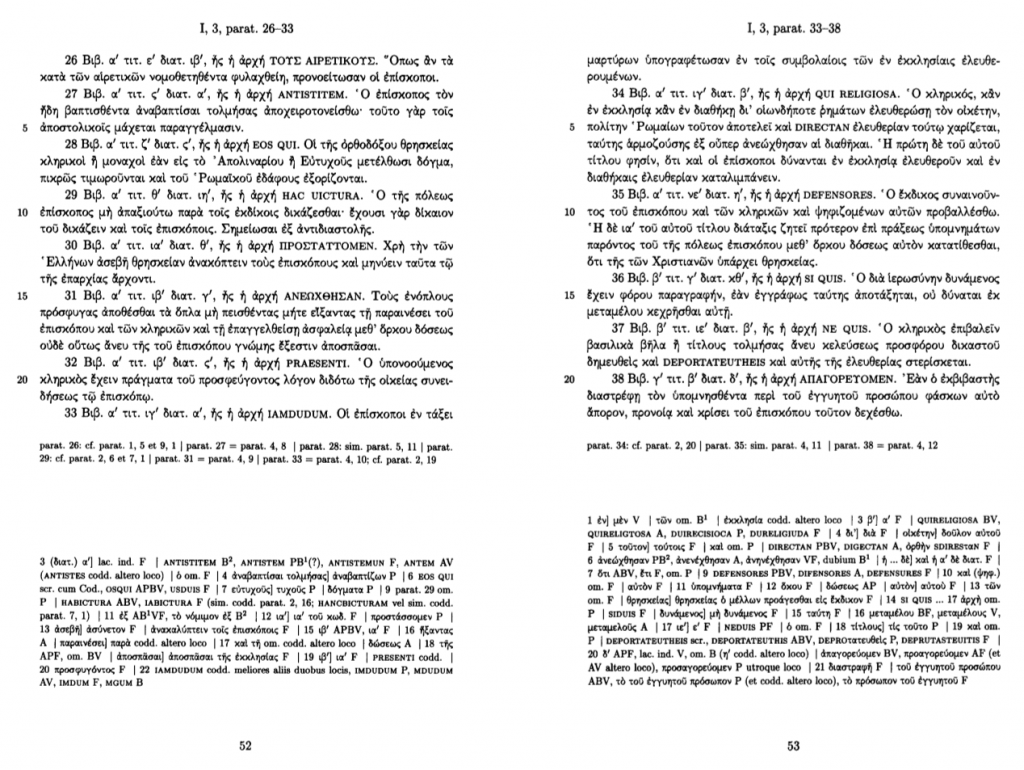

From Book 1.Title 3.Paratitla 32–34 of the Collectio Tripartita: Justinian on Religious and Ecclesiastical Affairs (B.H. Stolte and N. van der Wal, 1994)

A approximate translation would read:

(32) A cleric suspected of holding the affairs/possessions [πράγματα] of a refugee must give an account of his conscience to the bishop.

(33) Bishops, in the role of witnesses, shall sign [ὑπογραφέτωσαν] the contracts [συμβολαίοις] for those freed [ἐλευθερουμένων] in churches.

(34) A cleric, whether in church or by will, through any words [ῥημάτων], freeing [ἐλευθερώσῃ] a slave, makes him a Roman citizen and grants him direct freedom [ἐλευθερίαν], effective from when the wills were opened. The first ordinance of the same title states that bishops can also free [ἐλευθεροῦν] in church and leave freedom [ἐλευθερίαν] in wills.

Taking this into consideration (only to the degree that we can without much needed further study), it seems that the particular terms employed here in the Anaphora of St Gregory lean towards an additional layer of meaning, that is, the symbols (σὐμβολα)—bread and wine—are the contract to which the priest is steward/witness, and this contract is made based on the words (ῥήματα) of Christ Himself who sets us free from bitter bondage by His sacrifice, His body and blood (πράγματα). In other words, the bread and wine are the visible proof of the reality of our freedom in Christ which we may ascribe to the promise He made to His disciples, the contract so to speak, that they, the bread and wine, are truly His body and blood.

And this very notion, that the symbols of the bread and wine communicate to us visibly the hidden reality of the body and blood of our Lord, is prominent in the writings of the early Church Fathers.

From the Eclesiastical Hierarchy of Dionysius the Areopagite (Pseudo-Dionysius?) PG 3

Section I.

Here then, too, O excellent son, after the images, I come in due order and reverence to the Godlike reality of the archetypes, saying here to those yet being initiated, for the harmonious guidance of their souls, that the varied and sacred composition of the symbols is not without spiritual contemplation for them, as merely presented superficially. For the most sacred chants and readings of the Oracles teach them a discipline of a virtuous life, and previous to this, the, complete purification from destructive evil; and the most Divine, and common, and peaceful distribution of one and the same, both Bread and Cup, enjoins upon them a godly fellowship in character, as having a fellowship in food, and recalls to their memory the most Divine Supper, and arch-symbol of the rites performed, agreeably with which the Founder of the symbols Himself excludes, most justly, him who had supped with Him on the holy things, not piously and in a manner suitable to his character; teaching at once, clearly and Divinely, that the approach to Divine mysteries with a sincere mind confers, on those who draw nigh, the participation in a gift according to their own character.

Section II.

Let us, then, as I said, leave behind these things, beautifully depicted upon the entrance of the innermost shrine, as being sufficient for those, who are yet incomplete for contemplation, and let us proceed from the effects to the causes; and then, Jesus lighting the way, we shall view our holy Synaxis, and the comely contemplation of things intelligible, which makes radiantly manifest the blessed beauty of the archetypes. But, oh, most Divine and holy initiation, uncovering the folds of the dark mysteries enveloping thee in symbols, be manifest to us in thy bright glory, and fill our intellectual visions with single and unconcealed light. — John Parker, trans. 1894.

Cyril of Jerusalem’s Mystagogical Catacheses, 4 (https://azbyka.ru/otechnik/Kirill_Ierusalimskij/mystagogical-catecheses/#0_5):

John Chrysostom, Homily on Matthew, 82 (https://www.clerus.org/bibliaclerusonline/en/dli.htm):

Excerpt from Section 1:

“And as they were eating, He took bread, and brake it.” Why can it have been that He ordained this sacrament then, at the time of the passover? That thou mightest learn from everything, both that He is the lawgiver of the Old Testament, and that the things therein are foreshadowed because of these things. Therefore, I say, where the type is, there He puts the truth.

Excerpt from Section 4:

Let us then in everything believe God, and gainsay Him in nothing, though what is said seem to be contrary to our thoughts and senses, but let His word be of higher authority than both reasonings and sight. Thus let us do in the mysteries also, not looking at the things set before us, but keeping in mind His sayings.

For His word cannot deceive, but our senses are easily beguiled. That has never failed, but this in most things goes wrong. Since then the word says, This is my body, let us both be persuaded and believe, and look at it with the eyes of the mind.

For Christ has given nothing sensible, but though in things sensible yet all to be perceived by the mind. So also in baptism, the gift is bestowed by a sensible thing, that is, by water; but that which is done is perceived by the mind, the birth, I mean, and the renewal. For if you had been incorporeal, He would have delivered you the incorporeal gifts bare; but because the soul has been locked up in a body, He delivers you the things that the mind perceives, in things sensible.

How many now say, I would wish to see His form, the mark, His clothes, His shoes. Lo! You see Him, Thou touchest Him, you eat Him. And thou indeed desirest to see His clothes, but He gives Himself to you not to see only, but also to touch and eat and receive within you.

Once again, the aforementioned Greek terms appear in a letter attributed to the Meletius, Melkite Patriarch of Alexandria in the 16th century (Methodios, Letters of Meletius Pegas, Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria, 1970-1975 (repr. 1976)) [verification pending; out of print]:

“We receive what is given and spoken by the Savior plainly; but when He speaks to us through symbols [συμβόλων, symbolōn], we consider both the symbols [σύμβολα, symbola] and the realities [πράγματα, pragmata] of which they are symbols [σύμβολα, symbola]. As when the Word [Λόγος, Logos] calls Himself a cornerstone, door, or way in symbolic [συμβολικὴν, symbolikēn] theology, we find through reflection that He is these due to His likeness to them, signified by them. (225) But sometimes the symbols [σύμβολα, symbola] do not only show grace but also impart the grace they signify, as with the water in baptism; it does not only signify but also effects the purification it signifies, enriched with power by the Spirit’s descent through the divine word [λόγου, logou]. And the holy Myron: we find, as some say, both symbols [σύμβολα, symbola] and symbols [συμβόλων, symbolōn] represented through others, and symbols [σύμβολα, symbola] of realities [πραγμάτων, pragmatōn]. (230) For the forms preserved in the mystery are symbols [σύμβολα, symbola], but the body and blood are realities [πράγματα, pragmata]. These, in turn, are said to be symbols [σύμβολα, symbola] of Christ’s mystical body, the Church; thus, those who theologize, carefully considering the Savior’s words [λόγους, logous], must appropriately receive them in their meanings and not confuse what is said. (235) So when the Savior says, “I am the bread of life,” He symbolically [συμβολικῶς, symbolikōs] signifies Himself as the active source of life through the bread, as the bread of life, not as transformed into bread. But when He says of the bread and wine in the mystery of communion, “This is my body” and “This is my blood,” He thus signifies His flesh and blood through symbols [συμβόλων, symbolōn], so that the symbols [σύμβολα, symbola] themselves are appropriately flesh and blood; (240) for the bread is flesh, and the wine is blood; for these are truly transformed into those realities [πραγματικῶς, pragmatikōs].”

After the words of the fathers and doctors of the Church, I am in no place to share my own thoughts any further. I do, however, pray and implore you, my dear reader, to attend to the tradition of our ancestors, partake of the body and blood of our Lord as worthily as you are able, with contrition and with joy, knowing that our Savior has given us freedom from bondage by His body and blood which He offers to us in bread and wine!

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.